papyrus

« Ă€ propos d’une confusion tardive dans l’emploi de wnn (ĂŞtre) et wn (ouvrir) »

ENiM 1, 2008, p. 1-6.

Cet article est l’occasion de souligner qu’une combinaison de vignettes du Livre des Morts peut éclairer le contenu modifié d’une formule « canonique ». Ainsi, la substitution de wnn, « être, exister » par wn, « ouvrir », dans la formule 103 du LdM, relève de la proximité thématique des formules 91/92 et 103, reliées de façon iconique dans le P. Louvre E 17400.

Cet article est l’occasion de souligner qu’une combinaison de vignettes du Livre des Morts peut éclairer le contenu modifié d’une formule « canonique ». Ainsi, la substitution de wnn, « être, exister » par wn, « ouvrir », dans la formule 103 du LdM, relève de la proximité thématique des formules 91/92 et 103, reliées de façon iconique dans le P. Louvre E 17400.

This contribution is the reason for stressing that a combination of Book of the Dead vignettes can throw a light on the modified contents of a “canonical” spell. Thus, the substitution of wnn, “be, exist” by wn, “open”, in BD spell 103, belongs to the vicinity of the topics of spells 91/92 and 103, joined together in an iconic way in P. Louvre E 17400.

This contribution is the reason for stressing that a combination of Book of the Dead vignettes can throw a light on the modified contents of a “canonical” spell. Thus, the substitution of wnn, “be, exist” by wn, “open”, in BD spell 103, belongs to the vicinity of the topics of spells 91/92 and 103, joined together in an iconic way in P. Louvre E 17400.

Consulter cet article (51745) -

Consulter cet article (51745) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (29659)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (29659)

« L’amnistie dĂ©crĂ©tĂ©e en l’an 21 de PtolĂ©mĂ©e Épiphane (185/184 a. C.) »

ENiM 5, 2012, p. 151-165.

Deux sources mettent en évidence la proclamation d’une amnistie pénale en l’an 21 du règne de Ptolémée Épiphane et éclairent d’un jour nouveau la politique de pacification développée par ce souverain : il s’agit d’un passage du décret sacerdotal daté de l’an 23 de Ptolémée Épiphane (stèle Caire RT 2/3/25/7, l. 19 20 ; stèle Caire JE 44901, l. 11 12) et d’ordonnances royales contenues sur un papyrus grec (C. Ord. Ptol. n° 34 = P. Kroll + P. Palau Rib. inv. 172a et b) que nous proposons également de dater de l’an 21 d’Épiphane.

Deux sources mettent en évidence la proclamation d’une amnistie pénale en l’an 21 du règne de Ptolémée Épiphane et éclairent d’un jour nouveau la politique de pacification développée par ce souverain : il s’agit d’un passage du décret sacerdotal daté de l’an 23 de Ptolémée Épiphane (stèle Caire RT 2/3/25/7, l. 19 20 ; stèle Caire JE 44901, l. 11 12) et d’ordonnances royales contenues sur un papyrus grec (C. Ord. Ptol. n° 34 = P. Kroll + P. Palau Rib. inv. 172a et b) que nous proposons également de dater de l’an 21 d’Épiphane.

Two documents show the proclamation of a penal amnesty in the 21th year of the reign of Ptolemy Epiphanes and bring to light the pacification’s policy developed by this sovereign: there are an extract of the sacerdotal decree of the 23th year of Ptolemy Epiphanes (stele Kairo RT 2/3/25/7, l. 19 20 ; stele Kairo JE 44901) and royal ordinances on a greek papyrus (C. Ord. Ptol. n° 34 = P. Kroll + P. Palau Rib. inv. 172a et b) which we suggest to date from the 21th year of Ptolemy Epiphanes.

Two documents show the proclamation of a penal amnesty in the 21th year of the reign of Ptolemy Epiphanes and bring to light the pacification’s policy developed by this sovereign: there are an extract of the sacerdotal decree of the 23th year of Ptolemy Epiphanes (stele Kairo RT 2/3/25/7, l. 19 20 ; stele Kairo JE 44901) and royal ordinances on a greek papyrus (C. Ord. Ptol. n° 34 = P. Kroll + P. Palau Rib. inv. 172a et b) which we suggest to date from the 21th year of Ptolemy Epiphanes.

Consulter cet article (40142) -

Consulter cet article (40142) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (22678)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (22678)

« Le papyrus-Amulette de Lyon MusĂ©e des Beaux-Arts H 2425 »

ENiM 6, 2013, p. 159-168.

Édition du papyrus de Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts H 2425, document datant de l’époque ptolémaïque rédigé en hiératique avec la formule 100 du Livre des morts accompagnée de son illustration. L’étude de ce manuscrit donne l’occasion de revenir sur la fonction et l’utilisation de cette catégorie d’objets en contexte funéraire.

Édition du papyrus de Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts H 2425, document datant de l’époque ptolémaïque rédigé en hiératique avec la formule 100 du Livre des morts accompagnée de son illustration. L’étude de ce manuscrit donne l’occasion de revenir sur la fonction et l’utilisation de cette catégorie d’objets en contexte funéraire.

Edition of the papyrus Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts H 2425, which can be dated to the Ptolemaic period. It is written in hieratic and contains the Spell 100 of the Book of the Dead with her illustration. The study of this manuscript allows us to reconsider the function and use of this category of objects in funerary context.

Edition of the papyrus Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts H 2425, which can be dated to the Ptolemaic period. It is written in hieratic and contains the Spell 100 of the Book of the Dead with her illustration. The study of this manuscript allows us to reconsider the function and use of this category of objects in funerary context.

Consulter cet article (47381) -

Consulter cet article (47381) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (25027)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (25027)

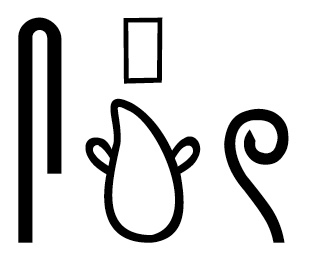

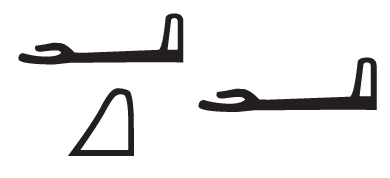

« Construire un bateau Ă l’orĂ©e des grands fourrĂ©s de papyrus. Ă€ propos du verbe  spj, “assembler (une embarcation)” »

spj, “assembler (une embarcation)” »

ENiM 11, 2018, p. 197-224.

Le verbe spj est habituellement traduit « attacher les parties d’un bateau en papyrus ou en bois ». Cependant, en raison du déterminatif très particulier qui accompagne ce mot, le signe N32 de la liste de Gardiner, qui figure une masse d’excréments ou d’argile, certains chercheurs on fait dériver le sens de ce mot d’un sens primitif signifiant « calfater ». Or, le calfatage est un technique apparaissant tardivement dans la construction des bateaux en bois. Ce signe figure en fait un mélange d’argile et de déjections de bovidés servant à colmater les parties faibles d’une coque en bois.

Le verbe spj est habituellement traduit « attacher les parties d’un bateau en papyrus ou en bois ». Cependant, en raison du déterminatif très particulier qui accompagne ce mot, le signe N32 de la liste de Gardiner, qui figure une masse d’excréments ou d’argile, certains chercheurs on fait dériver le sens de ce mot d’un sens primitif signifiant « calfater ». Or, le calfatage est un technique apparaissant tardivement dans la construction des bateaux en bois. Ce signe figure en fait un mélange d’argile et de déjections de bovidés servant à colmater les parties faibles d’une coque en bois.

The verb spj is usually translated as « to tie the parts of a boat in papyrus or wood ». However, because of the very particular determinative that accompanies this word, the N32 sign of Gardiner’s list, which is a mass of excrement or clay, some researchers have derived the meaning of this word from a primitive signification meaning « caulk ». However, caulking is a technique that appears late in the construction of wooden boats. This sign is a mixture of clay and dung of cattle used to seal the weak parts of a wooden hull.

The verb spj is usually translated as « to tie the parts of a boat in papyrus or wood ». However, because of the very particular determinative that accompanies this word, the N32 sign of Gardiner’s list, which is a mass of excrement or clay, some researchers have derived the meaning of this word from a primitive signification meaning « caulk ». However, caulking is a technique that appears late in the construction of wooden boats. This sign is a mixture of clay and dung of cattle used to seal the weak parts of a wooden hull.

Consulter cet article (42584) -

Consulter cet article (42584) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (22793)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (22793)

« Ă€ propos de  , ʿqʿ, “serrer” »

, ʿqʿ, “serrer” »

ENiM 11, 2018, p. 225-229.

Le mot ʿqʿ, qui accompagne les figurations de bateaux dans les mastabas de l’Ancien Empire, est habituellement traduit par « attacher ensemble (les parties d’un bateau) ». Cette traduction correspond plutĂ´t au mot spj, ʿqʿ dĂ©signant simplement l’action de serrer les cordes attachant ensemble les bottes de papyrus de la coque d’un bateau.

Le mot ʿqʿ, qui accompagne les figurations de bateaux dans les mastabas de l’Ancien Empire, est habituellement traduit par « attacher ensemble (les parties d’un bateau) ». Cette traduction correspond plutĂ´t au mot spj, ʿqʿ dĂ©signant simplement l’action de serrer les cordes attachant ensemble les bottes de papyrus de la coque d’un bateau.

The word ʿqʿ, which accompanies the figurations of boats in the mastabas of the Old Kingdom, is usually translated as « tie together (the parts of a boat) ». This translation corresponds rather to the word spj, ʿqʿ simply designating the action of tightening the ropes tying together the papyrus of the hull of a boat.

The word ʿqʿ, which accompanies the figurations of boats in the mastabas of the Old Kingdom, is usually translated as « tie together (the parts of a boat) ». This translation corresponds rather to the word spj, ʿqʿ simply designating the action of tightening the ropes tying together the papyrus of the hull of a boat.

Consulter cet article (40501) -

Consulter cet article (40501) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (23091)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (23091)

« Une introduction Ă la « formule pour prĂ©senter les offrandes » (en marge d’une publication prochaine, 1) »

ENiM 12, 2019, p. 181-200.

Essai de synthèse sur une formule religieuse dont les premières attestations remontent au tout début du Nouvel Empire, réalisé ici sur la base d’une version démotique conservée sur le P. Bodl. MS. Egypt. a.3(P). Le texte est dépourvu de titre, mais il s’agit, comme l’indiquent plusieurs parallèles, d’un des derniers témoins connus d’une « formule pour déposer les offrandes » (rA n wAH xwt). Son analyse linéaire, mais aussi l’examen des différents contextes où elle apparaît au cours de son histoire, permet d’en situer la lecture dans le calendrier religieux. La présence de cette formule dans le manuscrit d’Oxford à côté d’une version originale du Rituel de faire sortir Sokar de la STyt dont la lecture tombe le 25 Khoiak (date explicitement mentionnée en II, 1), ainsi que nombre d’éléments internes, confirment si besoin était son appartenance au corpus des rites osiriens de ce mois.

Essai de synthèse sur une formule religieuse dont les premières attestations remontent au tout début du Nouvel Empire, réalisé ici sur la base d’une version démotique conservée sur le P. Bodl. MS. Egypt. a.3(P). Le texte est dépourvu de titre, mais il s’agit, comme l’indiquent plusieurs parallèles, d’un des derniers témoins connus d’une « formule pour déposer les offrandes » (rA n wAH xwt). Son analyse linéaire, mais aussi l’examen des différents contextes où elle apparaît au cours de son histoire, permet d’en situer la lecture dans le calendrier religieux. La présence de cette formule dans le manuscrit d’Oxford à côté d’une version originale du Rituel de faire sortir Sokar de la STyt dont la lecture tombe le 25 Khoiak (date explicitement mentionnée en II, 1), ainsi que nombre d’éléments internes, confirment si besoin était son appartenance au corpus des rites osiriens de ce mois.

A summary report about a religious formula whose first attestations date back to the very beginning of the New Kingdom. The starting point for this study is a demotic version written on P. Bodl. MS. Egypt. a.3(P). The text is preceded by no title but it is, as shown by several parallels, one of the last known attestations of a “formula for presenting offerings” (rA n wAH xwt). Its linear analysis, but also examination of the different contexts in which it appears throughout its history, make it possible to situate the reading in the religious calendar. The presence of this formula in the Oxford manuscript next to an original version of the Ritual of bringing Sokar out of the STyt, read on 25 Khoiak (this date is explicitely specified in II, 1), as well as many internal elements, confirm if need be its place in the corpus of the rites performed that month.

A summary report about a religious formula whose first attestations date back to the very beginning of the New Kingdom. The starting point for this study is a demotic version written on P. Bodl. MS. Egypt. a.3(P). The text is preceded by no title but it is, as shown by several parallels, one of the last known attestations of a “formula for presenting offerings” (rA n wAH xwt). Its linear analysis, but also examination of the different contexts in which it appears throughout its history, make it possible to situate the reading in the religious calendar. The presence of this formula in the Oxford manuscript next to an original version of the Ritual of bringing Sokar out of the STyt, read on 25 Khoiak (this date is explicitely specified in II, 1), as well as many internal elements, confirm if need be its place in the corpus of the rites performed that month.

Consulter cet article (39963) -

Consulter cet article (39963) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (19701)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (19701)

« Les pyramides dans les problèmes mathĂ©matiques Ă©gyptiens »

ENiM 12, 2019, p. 233-246.

Le papyrus Rhind place les pyramides au centre de quelques problèmes en lien avec des calculs de seqed et de hauteur. Deux autres énoncés, les problèmes pRhind no 60 et pMoscou no 14, ont été maintes fois mis en parallèle avec ces derniers et commentés en raison des difficultés d’interprétation qu’ils suscitent. La terminologie employée, le contexte des exercices, mais aussi l’état de l’archéologie peuvent permettre d’identifier les constructions décrites. L’architecture autorise également quelques comparaisons significatives qui amènent à nous interroger sur l’une des sources d’inspiration des papyri mathématiques du Moyen Empire.

Le papyrus Rhind place les pyramides au centre de quelques problèmes en lien avec des calculs de seqed et de hauteur. Deux autres énoncés, les problèmes pRhind no 60 et pMoscou no 14, ont été maintes fois mis en parallèle avec ces derniers et commentés en raison des difficultés d’interprétation qu’ils suscitent. La terminologie employée, le contexte des exercices, mais aussi l’état de l’archéologie peuvent permettre d’identifier les constructions décrites. L’architecture autorise également quelques comparaisons significatives qui amènent à nous interroger sur l’une des sources d’inspiration des papyri mathématiques du Moyen Empire.

The Rhind mathematical papyrus incorporates a small group of problems focusing on pyramids and demonstrating how to calculate their seked side slopes and heights. Two other problems, pRhind 60 and pMoscow 14, have been discussed extensively in conjunction with the former problems due to the interpretive challenges they pose. The terminology they use and the context of the exercises mean that archaeology and philology can potentially provide information aiding understanding of the buildings described. Architecture uncovered in excavations may represent structures that inspired the problems outlined in the Middle Kingdom mathematical papyri, and the different classes of evidence are compared here.

The Rhind mathematical papyrus incorporates a small group of problems focusing on pyramids and demonstrating how to calculate their seked side slopes and heights. Two other problems, pRhind 60 and pMoscow 14, have been discussed extensively in conjunction with the former problems due to the interpretive challenges they pose. The terminology they use and the context of the exercises mean that archaeology and philology can potentially provide information aiding understanding of the buildings described. Architecture uncovered in excavations may represent structures that inspired the problems outlined in the Middle Kingdom mathematical papyri, and the different classes of evidence are compared here.

Consulter cet article (48051) -

Consulter cet article (48051) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (23919)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (23919)

« L’oiseau bĂ©nou-phĂ©nix et son tertre sur la tunique historiĂ©e de Saqqâra. Une interprĂ©tation nouvelle »

ENiM 12, 2019, p. 247-280.

Depuis la découverte en 1922 de la tunique historiée de Saqqâra, les études se sont succédé pour la dater et l’interpréter, sous différents angles. Dans ce document d’époque romaine, on a reconnu le bénou d’Héliopolis sur la butte de la création originelle. Mais l’iconographie de l’oiseau est influencée par le mythe gréco-romain du phénix, puisqu’un jeu de mots remplace le traditionnel héron cendré par un flamant rose, phoinikopteros, tel qu’il se voit aussi approximativement à la même époque sur la monnaie d’Hadrien intronisant le phénix comme symbole impérial ; il n’a pas un « bec de vautour » en référence au hiéroglyphe de l’année. Quant à la butte, son curieux décor ne montre ni « bandelettes sacrées », ni « flammes », ni « rochers » symbolisant les douze mois de l’année, mais treize plants de papyrus et les sept bouches du Nil, c’est-à -dire une image gréco-romaine du delta, dans une lecture topographique horizontale qui se superpose à la lecture verticale et temporelle.

Depuis la découverte en 1922 de la tunique historiée de Saqqâra, les études se sont succédé pour la dater et l’interpréter, sous différents angles. Dans ce document d’époque romaine, on a reconnu le bénou d’Héliopolis sur la butte de la création originelle. Mais l’iconographie de l’oiseau est influencée par le mythe gréco-romain du phénix, puisqu’un jeu de mots remplace le traditionnel héron cendré par un flamant rose, phoinikopteros, tel qu’il se voit aussi approximativement à la même époque sur la monnaie d’Hadrien intronisant le phénix comme symbole impérial ; il n’a pas un « bec de vautour » en référence au hiéroglyphe de l’année. Quant à la butte, son curieux décor ne montre ni « bandelettes sacrées », ni « flammes », ni « rochers » symbolisant les douze mois de l’année, mais treize plants de papyrus et les sept bouches du Nil, c’est-à -dire une image gréco-romaine du delta, dans une lecture topographique horizontale qui se superpose à la lecture verticale et temporelle.

Since the discovery in 1922 of the decorated tunic of Saqqâra, the studies followed one another for its datation and interpretation, under various angles. On this document from the Roman era, one recognized the benu of Heliopolis on the primeval hill of the creation. But the iconography of the bird is influenced by the Graeco-Roman myth of the phoenix, because a pun allows to replace the traditional grey heron (ardea cinerea) by a pink flamingo, phoinikopteros, as it can also be seen, approximately at the same time, on Hadrian's currency inaugurating the bird as an imperial symbol ; it does not have « the beak of a vulture » in reference to the hieroglyph of the year. As for the mound, its curious decoration does not show a « sacred garland », neither « flames » nor « rocks » symbolising the twelve months of the year, but thirteen stems of papyrus and the seven mouths of the Nile, that is an Graeco-Roman image of the delta, in a horizontal topographic reading superimposed upon the vertical and temporal reading.

Since the discovery in 1922 of the decorated tunic of Saqqâra, the studies followed one another for its datation and interpretation, under various angles. On this document from the Roman era, one recognized the benu of Heliopolis on the primeval hill of the creation. But the iconography of the bird is influenced by the Graeco-Roman myth of the phoenix, because a pun allows to replace the traditional grey heron (ardea cinerea) by a pink flamingo, phoinikopteros, as it can also be seen, approximately at the same time, on Hadrian's currency inaugurating the bird as an imperial symbol ; it does not have « the beak of a vulture » in reference to the hieroglyph of the year. As for the mound, its curious decoration does not show a « sacred garland », neither « flames » nor « rocks » symbolising the twelve months of the year, but thirteen stems of papyrus and the seven mouths of the Nile, that is an Graeco-Roman image of the delta, in a horizontal topographic reading superimposed upon the vertical and temporal reading.

Consulter cet article (40658) -

Consulter cet article (40658) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (20985)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (20985)

« The Papyrus CGT 54015 »

ENiM 15, 2022, p. 117-121.

L’article est consacré à un papyrus du musée égyptologique de Turin daté du Nouvel Empire. Il contient cinq fragments du bien connu « Conte de Sanehet (Sinouhé) ». Dans de nombreux cas, cette version correspond aux sources de cette période avec quelques variations. Une transcription hiéroglyphique accompagnée d’une traduction commentée et d’une photographie sont ici présentées.

L’article est consacré à un papyrus du musée égyptologique de Turin daté du Nouvel Empire. Il contient cinq fragments du bien connu « Conte de Sanehet (Sinouhé) ». Dans de nombreux cas, cette version correspond aux sources de cette période avec quelques variations. Une transcription hiéroglyphique accompagnée d’une traduction commentée et d’une photographie sont ici présentées.

The paper deals with a papyrus from the collection of the Egyptian Museum in Turin dated to the NK. It contains five fragments from the well-known “Story of Sanehet (Sinuhe)”. In many cases this version corresponds to the sources from this period with some variations. A hieroglyphic transcription, a commented translation, and a photography are presented.

The paper deals with a papyrus from the collection of the Egyptian Museum in Turin dated to the NK. It contains five fragments from the well-known “Story of Sanehet (Sinuhe)”. In many cases this version corresponds to the sources from this period with some variations. A hieroglyphic transcription, a commented translation, and a photography are presented.

Consulter cet article (36414) -

Consulter cet article (36414) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (13799)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (13799)

« The Saite Oracle Papyrus reconsidered. The oracle text and the localization of the cult of Montu-Re-Harakhty »

ENiM 17, 2024, p. 101-127.

Depuis sa première publication par R. Parker, le papyrus oraculaire de Brooklyn (P. Brooklyn 47.218.3) a longtemps été utilisé comme source principale pour les études socio-culturelles visant à identifier les dignitaires thébains des 25e-26e dynasties et à reconstituer leurs généalogies. En revisitant son texte d’oracle, la présente étude traite les circonstances de la consultation oraculaire et de son résultat puisque la pétition publique porte sur un transfert de service du culte d’Amon à celui de Montou, c’est-à -dire les deux divinités les plus importantes de Thèbes et sa région. Une attention particulière est attachée au toponyme Iwnw-Sma, désignant clairement le temple de Montou à Ermant et non à Karnak, ainsi qu’à d’autres sources contemporaines appartenant au personnel hermonthite du dieu.

Depuis sa première publication par R. Parker, le papyrus oraculaire de Brooklyn (P. Brooklyn 47.218.3) a longtemps été utilisé comme source principale pour les études socio-culturelles visant à identifier les dignitaires thébains des 25e-26e dynasties et à reconstituer leurs généalogies. En revisitant son texte d’oracle, la présente étude traite les circonstances de la consultation oraculaire et de son résultat puisque la pétition publique porte sur un transfert de service du culte d’Amon à celui de Montou, c’est-à -dire les deux divinités les plus importantes de Thèbes et sa région. Une attention particulière est attachée au toponyme Iwnw-Sma, désignant clairement le temple de Montou à Ermant et non à Karnak, ainsi qu’à d’autres sources contemporaines appartenant au personnel hermonthite du dieu.

Since its first publication by R. Parker, the Saite Oracle Papyrus (P. Brooklyn 47.218.3) has long been used as a primary source for socio-cultural studies aiming at identifying Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Dynasty Theban dignitaries and reconstructing their genealogies. By revisiting its main oracle text, the present study focuses on the circumstances of the oracular consultation and its outcome since the public petition is concerned with a transfer of service from the cult of Amun to that of Montu, i.e. the two most prominent deities of Thebes and its surroundings. Particular attention is paid to the toponym Iwnw-Sma, clearly designating the temple of Montu at Armant and not in Karnak, as well as other contemporary sources belonging to the personnel of the god at Armant.

Since its first publication by R. Parker, the Saite Oracle Papyrus (P. Brooklyn 47.218.3) has long been used as a primary source for socio-cultural studies aiming at identifying Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Dynasty Theban dignitaries and reconstructing their genealogies. By revisiting its main oracle text, the present study focuses on the circumstances of the oracular consultation and its outcome since the public petition is concerned with a transfer of service from the cult of Amun to that of Montu, i.e. the two most prominent deities of Thebes and its surroundings. Particular attention is paid to the toponym Iwnw-Sma, clearly designating the temple of Montu at Armant and not in Karnak, as well as other contemporary sources belonging to the personnel of the god at Armant.

Consulter cet article (23564) -

Consulter cet article (23564) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (8451)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (8451)

« RĂ©nĂ©noutet Ă la porte de la maison »

ENiM 18, 2025, p. 1-12.

La déesse-cobra Rénénoutet est invoquée dans une formule d’un papyrus de la collection Wilbour au Brooklyn Museum, un manuel de protection magique contre les animaux dangereux daté de l’Époque tardive. L’analyse de ce passage fournit l’occasion d’étudier un aspect sous-estimé de cette divinité, le plus souvent affectée à la sauvegarde et à la prospérité des réserves produits précieux et de nourriture. En faisant des parallèles avec d’autres mentions de Rénénoutet, en contexte funéraire ou dans le décorum des temples, on constate qu’elle est aussi une gardienne des portes, dont elle interdit l’accès aux reptiles néfastes, notamment depuis le sous-sol de la demeure. En cela, elle partage les caractéristiques d’une catégorie de bons génies ophidiens très répandue dans les sociétés anciennes. Elle transcende également les séparations théoriques entre les mondes funéraires, cultuels et domestiques, et entre religion officielle et cultes populaires.

La déesse-cobra Rénénoutet est invoquée dans une formule d’un papyrus de la collection Wilbour au Brooklyn Museum, un manuel de protection magique contre les animaux dangereux daté de l’Époque tardive. L’analyse de ce passage fournit l’occasion d’étudier un aspect sous-estimé de cette divinité, le plus souvent affectée à la sauvegarde et à la prospérité des réserves produits précieux et de nourriture. En faisant des parallèles avec d’autres mentions de Rénénoutet, en contexte funéraire ou dans le décorum des temples, on constate qu’elle est aussi une gardienne des portes, dont elle interdit l’accès aux reptiles néfastes, notamment depuis le sous-sol de la demeure. En cela, elle partage les caractéristiques d’une catégorie de bons génies ophidiens très répandue dans les sociétés anciennes. Elle transcende également les séparations théoriques entre les mondes funéraires, cultuels et domestiques, et entre religion officielle et cultes populaires.

The cobra-goddess Renenutet is invoked in a spell in a papyrus of the Wilbour collection at the Brooklyn Museum, a Late Period manual of magical protection against dangerous animals. Analysis of this passage provides an opportunity to study an underestimated aspect of this divinity, most often assigned to the safeguard and prosperity of storage facilities of precious products and food. By drawing parallels with other mentions of Renenutet, in funerary contexts or in temple decoration, we can see that she was also a gatekeeper, preventing harmful reptiles from entering, dwelling particularly in the house underground. In this, she shares the characteristics of a category of good ophidian genies that was widespread in ancient societies. She also transcends the theoretical separations between the funerary, cultic and domestic worlds, and between official religion and popular cults.

The cobra-goddess Renenutet is invoked in a spell in a papyrus of the Wilbour collection at the Brooklyn Museum, a Late Period manual of magical protection against dangerous animals. Analysis of this passage provides an opportunity to study an underestimated aspect of this divinity, most often assigned to the safeguard and prosperity of storage facilities of precious products and food. By drawing parallels with other mentions of Renenutet, in funerary contexts or in temple decoration, we can see that she was also a gatekeeper, preventing harmful reptiles from entering, dwelling particularly in the house underground. In this, she shares the characteristics of a category of good ophidian genies that was widespread in ancient societies. She also transcends the theoretical separations between the funerary, cultic and domestic worlds, and between official religion and popular cults.

Consulter cet article (11984) -

Consulter cet article (11984) -  Télécharger cet article au format pdf (4036)

Télécharger cet article au format pdf (4036)

ENiM 18 - 2025

5 article(s) - 2 avril 2025.

ENiM 1 à 18 (2008-2025) : 224 articles

4 569 365 téléchargements

9 240 867 consulations.

Index des auteurs

Mots clés

Derniers articles :

Robert Steven Bianchi

Duplication and Continuity

(ENiM 18, p. 13-36 — 11 mars 2025)

Frédéric Mougenot

Rénénoutet à la porte de la maison

(ENiM 18, p. 1-12 — 29 janvier 2025)

CENiM - Mise en ligne des volumes Ă©puisĂ©s :

Anne-Sophie von BOMHARD DĂ©cans Ă©gyptiens, CENiM 23, Montpellier, 2020 — (2020)

Anne-Sophie von BOMHARD DĂ©cans Ă©gyptiens, CENiM 23, Montpellier, 2020 — (2020)

Jean-Claude Grenier L'Osiris ANTINOOS, CENiM 1, Montpellier, 2008 — (26 dĂ©cembre 2008)

Jean-Claude Grenier L'Osiris ANTINOOS, CENiM 1, Montpellier, 2008 — (26 dĂ©cembre 2008)

TDENiM - Mise en ligne des volumes Ă©puisĂ©s :

Twitter

Twitter 3784924 visites - 783 visite(s) aujourd’hui - 34 connecté(s)

© ENiM - Une revue d’égyptologie sur internet

Équipe Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne - UMR 5140 - « Archéologie des Sociétés Méditerranéennes » (Cnrs) - Université Paul Valéry - Montpellier III

Contact

Contact

Abonnez-vous !

Abonnez-vous ! Équipe Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne

Équipe Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne UMR 5140 « Archéologie des Sociétés Méditerranéennes » (Cnrs)

UMR 5140 « Archéologie des Sociétés Méditerranéennes » (Cnrs) Université Paul Valéry - Montpellier III

Université Paul Valéry - Montpellier III