ENiM 1 (2008) ENiM 2 (2009) ENiM 3 (2010) ENiM 4 (2011) ENiM 5 (2012) ENiM 6 (2013) ENiM 7 (2014) ENiM 8 (2015) ENiM 9 (2016) ENiM 10 (2017) ENiM 11 (2018) ENiM 12 (2019) ENiM 13 (2020) ENiM 14 (2021) ENiM 15 (2022) ENiM 16 (2023) ENiM 17 (2024)

ENiM 1 - 2008 (ISSN 2102-6629)

Sommaire

Pages

1-6

Cet article est lâoccasion de souligner quâune combinaison de vignettes du Livre des Morts peut Ă©clairer le contenu modifiĂ© dâune formule « canonique ». Ainsi, la substitution de wnn, « ĂȘtre, exister » par wn, « ouvrir », dans la formule 103 du LdM, relĂšve de la proximitĂ© thĂ©matique des formules 91/92 et 103, reliĂ©es de façon iconique dans le P. Louvre E 17400.

Cet article est lâoccasion de souligner quâune combinaison de vignettes du Livre des Morts peut Ă©clairer le contenu modifiĂ© dâune formule « canonique ». Ainsi, la substitution de wnn, « ĂȘtre, exister » par wn, « ouvrir », dans la formule 103 du LdM, relĂšve de la proximitĂ© thĂ©matique des formules 91/92 et 103, reliĂ©es de façon iconique dans le P. Louvre E 17400.

This contribution is the reason for stressing that a combination of Book of the Dead vignettes can throw a light on the modified contents of a âcanonicalâ spell. Thus, the substitution of wnn, âbe, existâ by wn, âopenâ, in BD spell 103, belongs to the vicinity of the topics of spells 91/92 and 103, joined together in an iconic way in P. Louvre E 17400.

This contribution is the reason for stressing that a combination of Book of the Dead vignettes can throw a light on the modified contents of a âcanonicalâ spell. Thus, the substitution of wnn, âbe, existâ by wn, âopenâ, in BD spell 103, belongs to the vicinity of the topics of spells 91/92 and 103, joined together in an iconic way in P. Louvre E 17400.

Pages

7-14

Une enquĂȘte menĂ©e sur les Enfants d'Horus (HĂąpy, Douamoutef, ImsĂ©ti et QĂ©behsĂ©nouf ) dans les Textes des Pyramides permet de mettre en relief leur vĂ©ritable identitĂ© thĂ©ologique, leurs fonctions essentielles, ainsi que les correspondants que les Ăgyptiens leur avaient attribuĂ©s dans le ciel nocturne, au sein des constellations que nous nommons Orion et la Grande Ourse.

Une enquĂȘte menĂ©e sur les Enfants d'Horus (HĂąpy, Douamoutef, ImsĂ©ti et QĂ©behsĂ©nouf ) dans les Textes des Pyramides permet de mettre en relief leur vĂ©ritable identitĂ© thĂ©ologique, leurs fonctions essentielles, ainsi que les correspondants que les Ăgyptiens leur avaient attribuĂ©s dans le ciel nocturne, au sein des constellations que nous nommons Orion et la Grande Ourse.

A synthetic study of the Sons of Horus (HĂąpy, Duamutef, Imseti and Qebehsenuf) in the Pyramid Texts is proposed, showing their genuine theological nature, their main functions, and the celestial correspondants the Egyptian gave them in the night sky, inside the constellations we call Orion and Great Bear (Ursa Major).

A synthetic study of the Sons of Horus (HĂąpy, Duamutef, Imseti and Qebehsenuf) in the Pyramid Texts is proposed, showing their genuine theological nature, their main functions, and the celestial correspondants the Egyptian gave them in the night sky, inside the constellations we call Orion and Great Bear (Ursa Major).

Pages

15-28

Les mentions du terme neheh sont analysĂ©es dans quelques textes du Moyen Empire. Ce terme y dĂ©signe le « temps », en tant que flux Ă©troitement liĂ© Ă lâĂ©ternitĂ© et lâimmuabilitĂ© djet, ainsi quâĂ la pratique de la MaĂąt.

Les mentions du terme neheh sont analysĂ©es dans quelques textes du Moyen Empire. Ce terme y dĂ©signe le « temps », en tant que flux Ă©troitement liĂ© Ă lâĂ©ternitĂ© et lâimmuabilitĂ© djet, ainsi quâĂ la pratique de la MaĂąt.

The mentions of neheh are analyzed in some texts of the Middle Empire. This term appoints the « time », as stream strictly connected to the eternity and the stability djet, as well as to the practice of Maat.

The mentions of neheh are analyzed in some texts of the Middle Empire. This term appoints the « time », as stream strictly connected to the eternity and the stability djet, as well as to the practice of Maat.

ENiM 2 - 2009 (ISSN 2102-6629)

Sommaire

Pages

1-8

Lâostracon DeM 1046 prĂ©sente une formule magique au texte surprenant. De fait, le mĂ©decin-magicien ne sâadresse pas seulement au venin mais Ă©galement aux conduits du corps du patient ; ce qui tĂ©moigne dâune attention aux effets secondaires possibles du traitement appliquĂ© au patient. Ce phĂ©nomĂšne semble se retrouver dans dâautres textes, comme en tĂ©moignent notamment les deux parallĂšles des P. Turin 1993 et P. Chester-Beatty XI.

Lâostracon DeM 1046 prĂ©sente une formule magique au texte surprenant. De fait, le mĂ©decin-magicien ne sâadresse pas seulement au venin mais Ă©galement aux conduits du corps du patient ; ce qui tĂ©moigne dâune attention aux effets secondaires possibles du traitement appliquĂ© au patient. Ce phĂ©nomĂšne semble se retrouver dans dâautres textes, comme en tĂ©moignent notamment les deux parallĂšles des P. Turin 1993 et P. Chester-Beatty XI.

O. DeM 1046 presents two well known parallels: P. Turin 1993 and P. Chester-Beatty XI. From a synopsis presentation and the exhaustive study of this text, we can observe an interesting phenomenon: at the same time, the magician is asking the venom to go out of the patientâs body and the bodyâs vessels not to catch some disease due to the passage of venom. It looks like a representation of the concept of âside effectsâ.

O. DeM 1046 presents two well known parallels: P. Turin 1993 and P. Chester-Beatty XI. From a synopsis presentation and the exhaustive study of this text, we can observe an interesting phenomenon: at the same time, the magician is asking the venom to go out of the patientâs body and the bodyâs vessels not to catch some disease due to the passage of venom. It looks like a representation of the concept of âside effectsâ.

Pages

9-23

Lâanalyse de quelques passages du Rituel de lâEmbaumement (P. Boulaq III) permet de reconstituer le cycle du ba dans un contexte spĂ©cifique de momification et de comprendre la logique des traditions sur lesquelles il se fonde, rĂ©sultant de lâobservation minutieuse de la nature.

Lâanalyse de quelques passages du Rituel de lâEmbaumement (P. Boulaq III) permet de reconstituer le cycle du ba dans un contexte spĂ©cifique de momification et de comprendre la logique des traditions sur lesquelles il se fonde, rĂ©sultant de lâobservation minutieuse de la nature.

The analysis of some passages of the Embalming Ritual (P. Boulaq III) allows to reconstitute the cycle of the ba in a specific context of mummification and to understand the logic of the traditions on which it is based, resulting from the meticulous observation of the nature.

The analysis of some passages of the Embalming Ritual (P. Boulaq III) allows to reconstitute the cycle of the ba in a specific context of mummification and to understand the logic of the traditions on which it is based, resulting from the meticulous observation of the nature.

Pages

25-52

Les notions de « couleurs » dans lâĂgypte ancienne doivent ĂȘtre apprĂ©hendĂ©es non pas isolĂ©ment mais selon une approche structurale, Ă lâintĂ©rieur de systĂšmes complĂ©mentaires ou antinomiques. Lâanalyse du vaste corpus des Textes des Pyramides permet ainsi de mettre en Ă©vidence la spĂ©cificitĂ© et les implications idĂ©ologiques du rouge (dĂ©cher), qui sâoppose aux trois autres couleurs « fondamentales » que constituent le noir (kem), le blanc (hedj) et le vert (ouadj).

Les notions de « couleurs » dans lâĂgypte ancienne doivent ĂȘtre apprĂ©hendĂ©es non pas isolĂ©ment mais selon une approche structurale, Ă lâintĂ©rieur de systĂšmes complĂ©mentaires ou antinomiques. Lâanalyse du vaste corpus des Textes des Pyramides permet ainsi de mettre en Ă©vidence la spĂ©cificitĂ© et les implications idĂ©ologiques du rouge (dĂ©cher), qui sâoppose aux trois autres couleurs « fondamentales » que constituent le noir (kem), le blanc (hedj) et le vert (ouadj).

Concepts of âcolorsâ in the Egyptian language cannot be studied separately; they have to be delt with inside structural systems, either complementary or antinomic. Through the analysis of the large corpus of the Pyramid Texts, this paper tries to highlight the specificity and the ideological background of the red colour (decher), as opposed to three other âfundamentalâ colors: black (kem), white (hedj) and green (ouadj).

Concepts of âcolorsâ in the Egyptian language cannot be studied separately; they have to be delt with inside structural systems, either complementary or antinomic. Through the analysis of the large corpus of the Pyramid Texts, this paper tries to highlight the specificity and the ideological background of the red colour (decher), as opposed to three other âfundamentalâ colors: black (kem), white (hedj) and green (ouadj).

Pages

53-58

Cette brÚve note lexicographique concerne le terme ghr.t, attesté par quelques

exemples provenant des temples gréco-romains de la région thébaine et par le P. Carlsberg I,

qui conduit à une traduction plus précise : « voûte céleste septentrionale ».

Cette brÚve note lexicographique concerne le terme ghr.t, attesté par quelques

exemples provenant des temples gréco-romains de la région thébaine et par le P. Carlsberg I,

qui conduit à une traduction plus précise : « voûte céleste septentrionale ».

The subject of this short lexicographical note concerns the word ghr.t, attested in few

examples from the graeco-roman temples of the Theban area and in the P. Carlsberg I, which

leads to the most accurate translation âNortherly sky vaultâ.

The subject of this short lexicographical note concerns the word ghr.t, attested in few

examples from the graeco-roman temples of the Theban area and in the P. Carlsberg I, which

leads to the most accurate translation âNortherly sky vaultâ.

Pages

59-65

Ă lâAbbaye de Grottaferrata (Italie) sont visibles des fragments de reliefs Ă©gyptisants et la partie infĂ©rieure dâune statue de SĂ©thi I. Celle-ci fut apportĂ©e Ă lâĂ©poque romaine et provient du temple de RĂȘ Ă HĂ©liopolis. La publication rĂ©cente dâun catalogue des sculptures de lâAbbaye a Ă©tĂ© lâoccasion de rĂ©flĂ©chir sur le lieu d'origine et sur la signification de cette statue dans le milieu romain. Lâexistence dâune villa trĂšs importante dans les environs du chĂąteau de Borghetto, oĂč la statue a Ă©tĂ© trouvĂ©e, permet de proposer l'hypothĂšse quâelle y Ă©tait placĂ©e. Il est possible dâattribuer cette villa Ă L. Funisulanus Vettonianus, important personnage du temps de Domitien, qui Ă©tait apparentĂ© Ă Funisulana Vettulla, femme de C. Tettius Africanus, prĂ©fet dâĂgypte sous Domitien.

Ă lâAbbaye de Grottaferrata (Italie) sont visibles des fragments de reliefs Ă©gyptisants et la partie infĂ©rieure dâune statue de SĂ©thi I. Celle-ci fut apportĂ©e Ă lâĂ©poque romaine et provient du temple de RĂȘ Ă HĂ©liopolis. La publication rĂ©cente dâun catalogue des sculptures de lâAbbaye a Ă©tĂ© lâoccasion de rĂ©flĂ©chir sur le lieu d'origine et sur la signification de cette statue dans le milieu romain. Lâexistence dâune villa trĂšs importante dans les environs du chĂąteau de Borghetto, oĂč la statue a Ă©tĂ© trouvĂ©e, permet de proposer l'hypothĂšse quâelle y Ă©tait placĂ©e. Il est possible dâattribuer cette villa Ă L. Funisulanus Vettonianus, important personnage du temps de Domitien, qui Ă©tait apparentĂ© Ă Funisulana Vettulla, femme de C. Tettius Africanus, prĂ©fet dâĂgypte sous Domitien.

Three fragments of Egyptianizing reliefs and the bottom part of a statue of Sethi I are preserved in the Abbey of Grottaferrata (Italy). A catalog has recently been published highlighting new data about how the statue from Heliopolis ended up in a Roman context. In the neighbourhood of Borghetto Castle, where the statue was found, there was an important villa, probably belonging to L. Funisulanus Vettonianus, a relative of Funisulana Vettulla, the wife of C. Tettius Africanus, Prefect of Egypt.

Three fragments of Egyptianizing reliefs and the bottom part of a statue of Sethi I are preserved in the Abbey of Grottaferrata (Italy). A catalog has recently been published highlighting new data about how the statue from Heliopolis ended up in a Roman context. In the neighbourhood of Borghetto Castle, where the statue was found, there was an important villa, probably belonging to L. Funisulanus Vettonianus, a relative of Funisulana Vettulla, the wife of C. Tettius Africanus, Prefect of Egypt.

Pages

67-90

ComplĂ©ment Ă lâinventaire des cultes dâAmon Ă Memphis datant du Nouvel Empire. Celui-ci comprend cinq formes supplĂ©mentaires, une liste des formes dâAmon «indĂ©terminĂ©es» et un supplĂ©ment aux formes dâAmon dĂ©jĂ connues.

Cette note est suivie d'une liste des monuments d'origine memphite victimes de martelages Ă lâĂ©poque amarnienne.

ComplĂ©ment Ă lâinventaire des cultes dâAmon Ă Memphis datant du Nouvel Empire. Celui-ci comprend cinq formes supplĂ©mentaires, une liste des formes dâAmon «indĂ©terminĂ©es» et un supplĂ©ment aux formes dâAmon dĂ©jĂ connues.

Cette note est suivie d'une liste des monuments d'origine memphite victimes de martelages Ă lâĂ©poque amarnienne.

Complement to the inventory of worships of Amun in Memphis during the New Kingdom. This includes five additional forms, a list of âundeterminedâ Amun and a supplement to the Amun who are already known.

This note is follow by a list of the monuments of Memphis which are the victim of erasure during the Amarna period.

Complement to the inventory of worships of Amun in Memphis during the New Kingdom. This includes five additional forms, a list of âundeterminedâ Amun and a supplement to the Amun who are already known.

This note is follow by a list of the monuments of Memphis which are the victim of erasure during the Amarna period.

Pages

91-101

Les historiens antiques et Ă leur suite, un grand nombre d'historiens modernes, ont sĂ©vĂšrement critiquĂ© le quatriĂšme souverain de l'Ăgypte hellĂ©nistique, PtolĂ©mĂ©e Philopator, et au delĂ de la figure historique, leur jugement s'est naturellement focalisĂ© sur le bilan de son rĂšgne. Cet Ă©tat de fait tient en grande partie Ă la tradition transmise par Polybe et reprise par ses successeurs. Cependant, une remise en question de cette vision trop nĂ©gative est perceptible depuis une quarantaine dÂŽannĂ©es grĂące Ă une relecture des sources et Ă une analyse nouvelle des faits (dont certains inconnus des historiens de la premiĂšre moitiĂ© du XXe siĂšcle). Cet article propose de faire un point sur cette question.

Les historiens antiques et Ă leur suite, un grand nombre d'historiens modernes, ont sĂ©vĂšrement critiquĂ© le quatriĂšme souverain de l'Ăgypte hellĂ©nistique, PtolĂ©mĂ©e Philopator, et au delĂ de la figure historique, leur jugement s'est naturellement focalisĂ© sur le bilan de son rĂšgne. Cet Ă©tat de fait tient en grande partie Ă la tradition transmise par Polybe et reprise par ses successeurs. Cependant, une remise en question de cette vision trop nĂ©gative est perceptible depuis une quarantaine dÂŽannĂ©es grĂące Ă une relecture des sources et Ă une analyse nouvelle des faits (dont certains inconnus des historiens de la premiĂšre moitiĂ© du XXe siĂšcle). Cet article propose de faire un point sur cette question.

The ancient historians and at their turn, a large number of modern historians have severely criticized the forth sovereign of Hellenistic Egypt, Ptolemy IV Philopator and beyond the historic figure, they based their judgment on the facts of his reign. This situation is, in large part, the result of the tradition transmitted by Polybius and taken over by his successors. Nevertheless, this very negative perspective has been looked at differently during the last forty years due to reviewing the sources and reanalyzing the facts (some of which were unknown to the historians of the first half of the 20th century). This article aims to make a point in this matter.

The ancient historians and at their turn, a large number of modern historians have severely criticized the forth sovereign of Hellenistic Egypt, Ptolemy IV Philopator and beyond the historic figure, they based their judgment on the facts of his reign. This situation is, in large part, the result of the tradition transmitted by Polybius and taken over by his successors. Nevertheless, this very negative perspective has been looked at differently during the last forty years due to reviewing the sources and reanalyzing the facts (some of which were unknown to the historians of the first half of the 20th century). This article aims to make a point in this matter.

Pages

103-108

Un nouvel examen de blocs de granite dĂ©couverts Ă Tell FarĂąoun/Nebesheh par Petrie permet de prĂ©ciser lâattribution du petit temple de lâancienne ville dâImet. Leur identification Ă deux montants de porte confirme la premiĂšre impression que pouvait laisser la configuration des lieux, Ă savoir que le petit temple dâImet ne serait pas la demeure de la dĂ©esse principale, Ouadjet dame dâImet, mais celle de Min. LâĂ©poque Ă laquelle remonte ce temple, parfaitement datĂ© par un dĂ©pĂŽt de fondation du roi Amasis (XXVIe dyn.), correspond Ă celle oĂč le dieu Min dâImet apparaĂźt dans la documentation.

Un nouvel examen de blocs de granite dĂ©couverts Ă Tell FarĂąoun/Nebesheh par Petrie permet de prĂ©ciser lâattribution du petit temple de lâancienne ville dâImet. Leur identification Ă deux montants de porte confirme la premiĂšre impression que pouvait laisser la configuration des lieux, Ă savoir que le petit temple dâImet ne serait pas la demeure de la dĂ©esse principale, Ouadjet dame dâImet, mais celle de Min. LâĂ©poque Ă laquelle remonte ce temple, parfaitement datĂ© par un dĂ©pĂŽt de fondation du roi Amasis (XXVIe dyn.), correspond Ă celle oĂč le dieu Min dâImet apparaĂźt dans la documentation.

The reconsideration of granite fragments unearthed by Petrie at Tell Farʿun / Nebesheh allows us to clarify the attribution of the small temple of the ancient town of Imet. Their identification to two door-jambs confirms the first impression that could give the field, namely that the small temple is not the place of worship of Wadjet of Imet, the main deity, but the one of Min. The date of the construction of this temple, given by a foundation deposit of Amasis (26th dyn.), coincides with the date of the apparition of Min of Imet in the documentation.

The reconsideration of granite fragments unearthed by Petrie at Tell Farʿun / Nebesheh allows us to clarify the attribution of the small temple of the ancient town of Imet. Their identification to two door-jambs confirms the first impression that could give the field, namely that the small temple is not the place of worship of Wadjet of Imet, the main deity, but the one of Min. The date of the construction of this temple, given by a foundation deposit of Amasis (26th dyn.), coincides with the date of the apparition of Min of Imet in the documentation.

Pages

109-128

Lâanalyse du cercueil de Pȝ-n(y)-jw (XXXe dyn. â dĂ©but de lâĂ©poque ptolĂ©maĂŻque ; MusĂ©e dâhistoire naturelle de Santiago du Chili â MNHN 11.160) permet de mettre en lumiĂšre lâemploi dâune boiserie en trompe-lâĆil originale et son rapport avec diffĂ©rents motifs religieux, notamment deux figures dâAnubis anthropomorphe adoptant la posture ksw.

Lâanalyse du cercueil de Pȝ-n(y)-jw (XXXe dyn. â dĂ©but de lâĂ©poque ptolĂ©maĂŻque ; MusĂ©e dâhistoire naturelle de Santiago du Chili â MNHN 11.160) permet de mettre en lumiĂšre lâemploi dâune boiserie en trompe-lâĆil originale et son rapport avec diffĂ©rents motifs religieux, notamment deux figures dâAnubis anthropomorphe adoptant la posture ksw.

The analysis of the Pȝ-n(y)-jwâs coffin (Dynasty 30 â Ptolemaic Period; Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Santiago of Chile â MNHN 11.160) allows to throw a light on the use of an original woodwork in trompe lâoeil and his relationship with various religious motives, specially two anthropomorphic Anubis in the ksw posture.

The analysis of the Pȝ-n(y)-jwâs coffin (Dynasty 30 â Ptolemaic Period; Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Santiago of Chile â MNHN 11.160) allows to throw a light on the use of an original woodwork in trompe lâoeil and his relationship with various religious motives, specially two anthropomorphic Anubis in the ksw posture.

Pages

129-154

La stĂšle Madrid 1999/99/4 est republiĂ©e, accompagnĂ©e dâun commentaire philologique et historique. Il sâagit en fait dâune stĂšle de donation, la plus ancienne actuellement connue et datant dâun roi de la fin de la XIIIe dynastie nommĂ© SĂ©hĂ©qa-en-RĂȘ SĂ©ankhi-Ptah.

Une bibliographie mise Ă jour de toutes les stĂšles de donation connues est donnĂ©e en appendice Ă lâarticle.

La stĂšle Madrid 1999/99/4 est republiĂ©e, accompagnĂ©e dâun commentaire philologique et historique. Il sâagit en fait dâune stĂšle de donation, la plus ancienne actuellement connue et datant dâun roi de la fin de la XIIIe dynastie nommĂ© SĂ©hĂ©qa-en-RĂȘ SĂ©ankhi-Ptah.

Une bibliographie mise Ă jour de toutes les stĂšles de donation connues est donnĂ©e en appendice Ă lâarticle.

The stela Madrid 1999/99/4 is published anew with a philological and historical commentary. It appears to be the oldest donation stela known yet, dated to the first year of a king named Seheqa-en-Re Seankhi-Ptah, probably of the end of the XIIIth Dynasty. An updated bibliography of all known donation stelae is appended to the article.

The stela Madrid 1999/99/4 is published anew with a philological and historical commentary. It appears to be the oldest donation stela known yet, dated to the first year of a king named Seheqa-en-Re Seankhi-Ptah, probably of the end of the XIIIth Dynasty. An updated bibliography of all known donation stelae is appended to the article.

Pages

155-163

Publication dâun petit bronze inĂ©dit (Ăgypte, Ă©poque ptolĂ©maĂŻque ?) montrant AmmĂŽn coiffĂ© de la couronne dâAmon et tenant un sceptre ouas. En appendice, la publication dâune tĂȘte en marbre dâAmmĂŽn (Ăgypte, IIe s. ap. J.-.C.).

Publication dâun petit bronze inĂ©dit (Ăgypte, Ă©poque ptolĂ©maĂŻque ?) montrant AmmĂŽn coiffĂ© de la couronne dâAmon et tenant un sceptre ouas. En appendice, la publication dâune tĂȘte en marbre dâAmmĂŽn (Ăgypte, IIe s. ap. J.-.C.).

Publication of a small unpublished bronze (Egypt, Ptolemaic Period?) of AmmĂŽn wearing Amonâs crown and holding the was-scepter. In Appendix, the publication of a marble head of AmmĂŽn (Egypt, second century AD.).

Publication of a small unpublished bronze (Egypt, Ptolemaic Period?) of AmmĂŽn wearing Amonâs crown and holding the was-scepter. In Appendix, the publication of a marble head of AmmĂŽn (Egypt, second century AD.).

ENiM 3 - 2010 (ISSN 2102-6629)

Sommaire

Pages

1-21

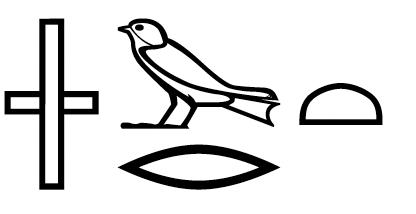

LâĂ©pithĂšte jwʿw nḥḥ, lâ « hĂ©ritier du temps », renvoie essentiellement Ă Osiris ou Ă la divinitĂ© solaire dans certains de ses aspects. Il sâagit dâune divinitĂ© qui se rĂ©gĂ©nĂšre pĂ©riodiquement en dĂ©butant rĂ©guliĂšrement un nouveau cycle temporel neheh annuel ou diurne.

LâĂ©pithĂšte jwʿw nḥḥ, lâ « hĂ©ritier du temps », renvoie essentiellement Ă Osiris ou Ă la divinitĂ© solaire dans certains de ses aspects. Il sâagit dâune divinitĂ© qui se rĂ©gĂ©nĂšre pĂ©riodiquement en dĂ©butant rĂ©guliĂšrement un nouveau cycle temporel neheh annuel ou diurne.

The attribute jwʿw nḥḥ, the « Heir of time », refers essentially to Osiris or to the solar divinity under some of its aspects. It is a divinity who regenerates periodically herself beginning regularly a new temporal cycle neheh annual or diurnal.

The attribute jwʿw nḥḥ, the « Heir of time », refers essentially to Osiris or to the solar divinity under some of its aspects. It is a divinity who regenerates periodically herself beginning regularly a new temporal cycle neheh annual or diurnal.

Pages

23-42

Publication dâune brique magique occidentale anonyme conservĂ©e au musĂ©e de Birmingham (1969 W 478). AprĂšs examen, il apparaĂźt que la brique nâĂ©tait pas anonyme dĂšs sa conception mais que le nom du bĂ©nĂ©ficiaire a Ă©tĂ© perdu. En dĂ©pit de la perte de la sĂ©quence nominative, lâĂ©tude typologique et textuelle de la brique permet de conclure que cet objet appartenait Ă un roi. La datation demeure incertaine.

Publication dâune brique magique occidentale anonyme conservĂ©e au musĂ©e de Birmingham (1969 W 478). AprĂšs examen, il apparaĂźt que la brique nâĂ©tait pas anonyme dĂšs sa conception mais que le nom du bĂ©nĂ©ficiaire a Ă©tĂ© perdu. En dĂ©pit de la perte de la sĂ©quence nominative, lâĂ©tude typologique et textuelle de la brique permet de conclure que cet objet appartenait Ă un roi. La datation demeure incertaine.

Publication of an anonymous western magical brick kept in Birmingham Museum (1969 W 478). A close examination shows that the object was not originally anonymous and that the name of the owner was lost. Despite of the lack of the ownerâs identity, the typological study of the brick and of its text allows to state that this object belonged to a royal funerary equipment. The datation remains uncertain.

Publication of an anonymous western magical brick kept in Birmingham Museum (1969 W 478). A close examination shows that the object was not originally anonymous and that the name of the owner was lost. Despite of the lack of the ownerâs identity, the typological study of the brick and of its text allows to state that this object belonged to a royal funerary equipment. The datation remains uncertain.

Pages

43-51

Quelques remarques concernant le fragment dâAthĂ©nĂ©e de Naucratis, Deipnosophistae XV, 677, en particulier la plante Chelidonium. Chelidonium corniculatum (L.) qui, en raison de la coloration sombre de ses feuilles, annonce la mort dâAntinoos.

Quelques remarques concernant le fragment dâAthĂ©nĂ©e de Naucratis, Deipnosophistae XV, 677, en particulier la plante Chelidonium. Chelidonium corniculatum (L.) qui, en raison de la coloration sombre de ses feuilles, annonce la mort dâAntinoos.

Some reflections about Athenaeusâfragments in Deipnosophistae XV, 677, and specially the plant called Chelidonium. Chelidonium corniculatum (L.) fortells Antinoosâ death due to the fact that the leaves coloration is glaucous.

Some reflections about Athenaeusâfragments in Deipnosophistae XV, 677, and specially the plant called Chelidonium. Chelidonium corniculatum (L.) fortells Antinoosâ death due to the fact that the leaves coloration is glaucous.

Pages

53-66

Deux formules magiques tirĂ©es dâun texte mĂ©dical du dĂ©but du Nouvel Empire mentionnent un dieu surnommĂ© par les Ăgyptiens « celui de lâĂ©tranger », apparemment liĂ© Ă une fĂ©dĂ©ration de tribus appartenant au groupe des Shosou. Ce dieu Ă©tait adorĂ© dans une contrĂ©e Ă©trangĂšre appelĂ©e OuĂąn, que lâon peut situer en Ădom. Dieu unique particuliĂšrement violent, il Ă©tait identifiĂ© dans la phrasĂ©ologie magique Ă©gyptienne au dieu BĂ©bon, forme sĂ©thienne du dieu Thot.

Deux formules magiques tirĂ©es dâun texte mĂ©dical du dĂ©but du Nouvel Empire mentionnent un dieu surnommĂ© par les Ăgyptiens « celui de lâĂ©tranger », apparemment liĂ© Ă une fĂ©dĂ©ration de tribus appartenant au groupe des Shosou. Ce dieu Ă©tait adorĂ© dans une contrĂ©e Ă©trangĂšre appelĂ©e OuĂąn, que lâon peut situer en Ădom. Dieu unique particuliĂšrement violent, il Ă©tait identifiĂ© dans la phrasĂ©ologie magique Ă©gyptienne au dieu BĂ©bon, forme sĂ©thienne du dieu Thot.

Two magic formulas taken from a medical text dating from the beginning of the New Kingdom refer to a god whom the Egyptians called âHe from the foreign countriesâ apparently a divinity linked to a federation of tribes belonging to the Shosou group. This god was worshipped in a foreign land called OuĂąn, somewhere in the region of Edom. This god unique and particularly violent was identified in magic Egyptian phraseology as the god Bebon, the sethian form of the god Thot.

Two magic formulas taken from a medical text dating from the beginning of the New Kingdom refer to a god whom the Egyptians called âHe from the foreign countriesâ apparently a divinity linked to a federation of tribes belonging to the Shosou group. This god was worshipped in a foreign land called OuĂąn, somewhere in the region of Edom. This god unique and particularly violent was identified in magic Egyptian phraseology as the god Bebon, the sethian form of the god Thot.

Pages

67-75

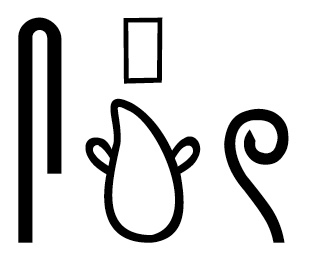

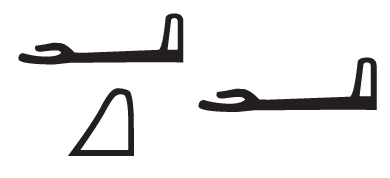

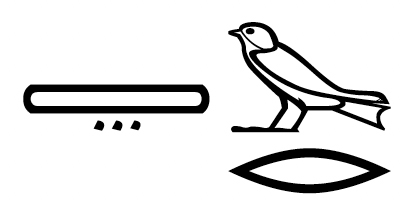

Analyse de deux orthographes non reconnues auparavant du nom Khepri. Le premier exemple est gĂ©nĂ©ralement Ă©crit « gorge et Ćil », la lecture repose pratiquement entiĂšrement sur le contexte. Le second est le trigramme bien connu « lotus-lion-bĂ©lier», qui pourrait designer Khepri comme le pendant logique dâAtoum, le dieu reprĂ©sentĂ© dans lâautre trigramme.

Analyse de deux orthographes non reconnues auparavant du nom Khepri. Le premier exemple est gĂ©nĂ©ralement Ă©crit « gorge et Ćil », la lecture repose pratiquement entiĂšrement sur le contexte. Le second est le trigramme bien connu « lotus-lion-bĂ©lier», qui pourrait designer Khepri comme le pendant logique dâAtoum, le dieu reprĂ©sentĂ© dans lâautre trigramme.

Discussion of two previously unrecognized orthographies of the name Khepri. The first example is written generally as âthroat and eye,â and the reading is established almost entirely from context. The second is the well-known trigram âlotus-lion-ram,â which could designate Khepri as the logical pendant of Atum, the god represented in the other trigram.

Discussion of two previously unrecognized orthographies of the name Khepri. The first example is written generally as âthroat and eye,â and the reading is established almost entirely from context. The second is the well-known trigram âlotus-lion-ram,â which could designate Khepri as the logical pendant of Atum, the god represented in the other trigram.

Pages

77-107

Lâinvention de la figure osirienne et de sa thĂ©ologie, probablement au dĂ©but de la Ve dynastie, fut un Ă©vĂ©nement considĂ©rable dans lâhistoire Ă©gyptienne, dont lâimpact dĂ©passa mĂȘme le cadre strict de lâĂtat pharaonique. On tente de montrer ici que les Textes des Pyramides, dans un grand nombre de formules, permettent de prĂ©ciser les modalitĂ©s institutionnelles et les motivations politiques de lâinstauration et de la diffusion de la doctrine osirienne.

Lâinvention de la figure osirienne et de sa thĂ©ologie, probablement au dĂ©but de la Ve dynastie, fut un Ă©vĂ©nement considĂ©rable dans lâhistoire Ă©gyptienne, dont lâimpact dĂ©passa mĂȘme le cadre strict de lâĂtat pharaonique. On tente de montrer ici que les Textes des Pyramides, dans un grand nombre de formules, permettent de prĂ©ciser les modalitĂ©s institutionnelles et les motivations politiques de lâinstauration et de la diffusion de la doctrine osirienne.

The invention of the Osirian figure and his theology, probably at the beginning of the 5th Dynasty, has been a considerable event in Egyptian history, whose impact exceeded largely Pharaonic State borders. The aim of this paper is to show to what extent, through a large number of Spells, the Pyramid Texts make it possible to specify the institutional ways and the political motivations of the introduction and the diffusion of the Osirian dogma.

The invention of the Osirian figure and his theology, probably at the beginning of the 5th Dynasty, has been a considerable event in Egyptian history, whose impact exceeded largely Pharaonic State borders. The aim of this paper is to show to what extent, through a large number of Spells, the Pyramid Texts make it possible to specify the institutional ways and the political motivations of the introduction and the diffusion of the Osirian dogma.

Pages

109-136

Les vases Ă figuration de BĂšs sont, Ă ce jour, notablement attestĂ©s dans les contextes stratigraphiques de Tell el-Herr (situĂ© dans la partie septentrionale de la pĂ©ninsule sinaĂŻtique), quâils soient de nature domestique, militaire ou cultuelle. Leur pĂ©rennitĂ© sur plusieurs dĂ©cennies dâoccupation du site permet dorĂ©navant une classification fine des vaisselles spĂ©cifiques de la pĂ©riode qui nous intĂ©resse ici : la pĂ©riode qui sâĂ©chelonne du milieu du Ve siĂšcle au premier quart du IVe siĂšcle av. n.Ăš. Parmi les formes identifiĂ©es, certaines dâentre elles se dĂ©marquent, outre par leur dĂ©cor, par leur profil atypique. Cette contribution met en avant quatre vases dont la raretĂ© des tĂ©moignages tant en Ăgypte que dans les territoires limitrophes, tout comme le degrĂ© de raffinement avec lequel ces vases furent confectionnĂ©s, incitent Ă supposer que leur genĂšse participe peut-ĂȘtre dâun rĂ©pertoire autre que celui de la cĂ©ramique. Certaines caractĂ©ristiques autorisent des connexions avec le rĂ©pertoire de la vaisselle dâapparat en mĂ©tal, en pierre, ou en terre cuite.

Les vases Ă figuration de BĂšs sont, Ă ce jour, notablement attestĂ©s dans les contextes stratigraphiques de Tell el-Herr (situĂ© dans la partie septentrionale de la pĂ©ninsule sinaĂŻtique), quâils soient de nature domestique, militaire ou cultuelle. Leur pĂ©rennitĂ© sur plusieurs dĂ©cennies dâoccupation du site permet dorĂ©navant une classification fine des vaisselles spĂ©cifiques de la pĂ©riode qui nous intĂ©resse ici : la pĂ©riode qui sâĂ©chelonne du milieu du Ve siĂšcle au premier quart du IVe siĂšcle av. n.Ăš. Parmi les formes identifiĂ©es, certaines dâentre elles se dĂ©marquent, outre par leur dĂ©cor, par leur profil atypique. Cette contribution met en avant quatre vases dont la raretĂ© des tĂ©moignages tant en Ăgypte que dans les territoires limitrophes, tout comme le degrĂ© de raffinement avec lequel ces vases furent confectionnĂ©s, incitent Ă supposer que leur genĂšse participe peut-ĂȘtre dâun rĂ©pertoire autre que celui de la cĂ©ramique. Certaines caractĂ©ristiques autorisent des connexions avec le rĂ©pertoire de la vaisselle dâapparat en mĂ©tal, en pierre, ou en terre cuite.

The Bes figure vases have been, to this day, significantly attested in the stratigraphic contexts of Tell el-Herr (located in the northern part of the Sinaitic peninsula), whether of domestic, military or cultural nature. Their durability over several decades of occupancy of the site hence enables fine-tuned classification of the crockery specific to the period of interest here: the period ranging from the middle of the Vth century to the first quarter of the IVth century BC. Among the new shapes identified, some of them, in addition to their decoration, standing out by their atypical profile. This contribution highlights four vases whose the rarity of the testimonies in Egypt as well as in the boundary territories, just like the degree of refinement with which these vases were manufactured, lead to assume that their genesis may point to another repertoire as that of ceramic. Some characteristics suggest connections with the repertoire of metal, stone or earthen ceremonial crockery.

The Bes figure vases have been, to this day, significantly attested in the stratigraphic contexts of Tell el-Herr (located in the northern part of the Sinaitic peninsula), whether of domestic, military or cultural nature. Their durability over several decades of occupancy of the site hence enables fine-tuned classification of the crockery specific to the period of interest here: the period ranging from the middle of the Vth century to the first quarter of the IVth century BC. Among the new shapes identified, some of them, in addition to their decoration, standing out by their atypical profile. This contribution highlights four vases whose the rarity of the testimonies in Egypt as well as in the boundary territories, just like the degree of refinement with which these vases were manufactured, lead to assume that their genesis may point to another repertoire as that of ceramic. Some characteristics suggest connections with the repertoire of metal, stone or earthen ceremonial crockery.

Pages

137-165

Description de la partie centrale de la NĂ©cropole des vaches sacrĂ©es HĂ©sat dâAtfih, ancienne capitale de la 22e province de Haute-Ăgypte, lâune des Aphroditopolis de lâĂ©poque grecque. La MEFA a dĂ©gagĂ© la zone anciennement fouillĂ©e par Ahmed Moussa pour le compte du CSA, composĂ©e de deux sarcophages de vaches, datĂ©s de la fin de lâĂ©poque dynastique ou du dĂ©but de la pĂ©riode ptolĂ©maĂŻque. Les structures abritant les sarcophages utilisent des bocs provenant dâun Ă©difice plus ancien, appartenant probablement Ă Osorkon lâAncien (XXIe dynastie).

Description de la partie centrale de la NĂ©cropole des vaches sacrĂ©es HĂ©sat dâAtfih, ancienne capitale de la 22e province de Haute-Ăgypte, lâune des Aphroditopolis de lâĂ©poque grecque. La MEFA a dĂ©gagĂ© la zone anciennement fouillĂ©e par Ahmed Moussa pour le compte du CSA, composĂ©e de deux sarcophages de vaches, datĂ©s de la fin de lâĂ©poque dynastique ou du dĂ©but de la pĂ©riode ptolĂ©maĂŻque. Les structures abritant les sarcophages utilisent des bocs provenant dâun Ă©difice plus ancien, appartenant probablement Ă Osorkon lâAncien (XXIe dynastie).

Description of the central part of the necropolis of the sacred cows Hesat at Atfih, the ancient capital of the 22nd province of Upper Egypt, one of the Aphroditopolis of the Greek period. The MEFA has cleared the area previously excavated by Ahmed Moussa for the SCA, composed of two sarcophagi of cows, dating from the late-dynastic or early Ptolemaic period. The structures in which are incorporated the sarcophagi have been built with reused blocks from an older building, probably belonging to Osorkon the Elder (XXI Dynasty).

Description of the central part of the necropolis of the sacred cows Hesat at Atfih, the ancient capital of the 22nd province of Upper Egypt, one of the Aphroditopolis of the Greek period. The MEFA has cleared the area previously excavated by Ahmed Moussa for the SCA, composed of two sarcophagi of cows, dating from the late-dynastic or early Ptolemaic period. The structures in which are incorporated the sarcophagi have been built with reused blocks from an older building, probably belonging to Osorkon the Elder (XXI Dynasty).

Pages

167-176

Ă la suite des brillants travaux de S. Sauneron et J. Yoyotte sur lâicherou, cet article revient sur certains aspects. Des textes du temple dâHathor Ă Dendera mettent en lumiĂšre le rĂŽle rituel de « faire un icherou », dans le cadre de lâapaisement de la DĂ©esse Lointaine et du retour de la crue. Un Ă©missaire de Sekhmet, appelĂ© le « Faiseur-dâicherou », pourrait remplir la mĂȘme fonction : apaiser la dĂ©esse et lui offrir un lieu propice Ă la naissance de sa progĂ©niture. Lâorigine naturelle de lâicherou est liĂ©e Ă la crue, comme le rapportent les rĂ©cits mythologiques sur le creusement du lac de Mout Ă Karnak. Le lac fait rĂ©fĂ©rence aux mares dâeau apparaissant Ă la lisiĂšre du dĂ©sert, avant le gonflement du fleuve. Ce phĂ©nomĂšne correspond Ă la fonction mythologique de lâicherou dans lâapaisement et le retour de la DĂ©esse Lointaine, avant lâarrivĂ©e de la crue.

Ă la suite des brillants travaux de S. Sauneron et J. Yoyotte sur lâicherou, cet article revient sur certains aspects. Des textes du temple dâHathor Ă Dendera mettent en lumiĂšre le rĂŽle rituel de « faire un icherou », dans le cadre de lâapaisement de la DĂ©esse Lointaine et du retour de la crue. Un Ă©missaire de Sekhmet, appelĂ© le « Faiseur-dâicherou », pourrait remplir la mĂȘme fonction : apaiser la dĂ©esse et lui offrir un lieu propice Ă la naissance de sa progĂ©niture. Lâorigine naturelle de lâicherou est liĂ©e Ă la crue, comme le rapportent les rĂ©cits mythologiques sur le creusement du lac de Mout Ă Karnak. Le lac fait rĂ©fĂ©rence aux mares dâeau apparaissant Ă la lisiĂšre du dĂ©sert, avant le gonflement du fleuve. Ce phĂ©nomĂšne correspond Ă la fonction mythologique de lâicherou dans lâapaisement et le retour de la DĂ©esse Lointaine, avant lâarrivĂ©e de la crue.

Following the seminal work of S. Sauneron and J. Yoyotte about the isheru, this article focuses on some aspects. Some texts from the Hathorâs temple of Dendera describe the ritual function of âmaking an isheruâ, within the pacifying of the Far-Away Goddess and the return of the flood. One of the demons of Sekhmet, called the âMaker-of-isheruâ, could play the same role in both pacifying the goddess and giving her a favourable place to give birth to her offspring. The natural origin of isheru is linked to the flood, as it is reported in the mythological texts about the digging of the Moutâs lake at Karnak. The lake refers to ponds appearing in the edge of the desert, before the river starts to swell. This phenomenon corresponds to the mythological role of isheru in the pacifying and the return of the Far-Away Goddess, before the arrival of the flood.

Following the seminal work of S. Sauneron and J. Yoyotte about the isheru, this article focuses on some aspects. Some texts from the Hathorâs temple of Dendera describe the ritual function of âmaking an isheruâ, within the pacifying of the Far-Away Goddess and the return of the flood. One of the demons of Sekhmet, called the âMaker-of-isheruâ, could play the same role in both pacifying the goddess and giving her a favourable place to give birth to her offspring. The natural origin of isheru is linked to the flood, as it is reported in the mythological texts about the digging of the Moutâs lake at Karnak. The lake refers to ponds appearing in the edge of the desert, before the river starts to swell. This phenomenon corresponds to the mythological role of isheru in the pacifying and the return of the Far-Away Goddess, before the arrival of the flood.

Pages

177-187

La stĂšle Turin N 50049, dĂ©diĂ©e Ă Amenhotep Ier divinisĂ©, comporte, outre un petit hymne qui lui est adressĂ©, un dicton dont la traduction prĂ©sente de nombreuses difficultĂ©s. Lâensemble du texte est examinĂ© en dĂ©tail, traduit et commentĂ©, afin de replacer le dicton dans son contexte.

La stĂšle Turin N 50049, dĂ©diĂ©e Ă Amenhotep Ier divinisĂ©, comporte, outre un petit hymne qui lui est adressĂ©, un dicton dont la traduction prĂ©sente de nombreuses difficultĂ©s. Lâensemble du texte est examinĂ© en dĂ©tail, traduit et commentĂ©, afin de replacer le dicton dans son contexte.

Stela N 50049 of the Turin Museum, dedicated to Amenophis I deified contains, besides a little hymn addressed to him, a saying whose translation presents many difficulties. The whole text is examined in detail, translated and commented, in order to set it back in context.

Stela N 50049 of the Turin Museum, dedicated to Amenophis I deified contains, besides a little hymn addressed to him, a saying whose translation presents many difficulties. The whole text is examined in detail, translated and commented, in order to set it back in context.

Pages

189-192

Une Ă©tiquette en ivoire reliĂ©e Ă une jarre provenant de la tombe du roi Scorpion, Ă Abydos, et datant de Nagada III, est le support dâune gravure reprĂ©sentant un animal Ă©nigmatique. Cet animal a dĂ©jĂ Ă©tĂ© dĂ©signĂ© comme Ă©tant un oryctĂ©rope, Orycteropus afer, car il possĂšde indubitablement des caractĂšres anatomiques appartenant Ă cette espĂšce. Toutefois, il prĂ©sente Ă©galement des caractĂšres anatomiques de fennec, Fennecus zerda. Cette derniĂšre possibilitĂ© dâinterprĂ©tation en ferait alors la seule reprĂ©sentation connue Ă ce jour de fennec en Ăgypte pour les Ă©poques prĂ©dynastique et pharaonique.

Une Ă©tiquette en ivoire reliĂ©e Ă une jarre provenant de la tombe du roi Scorpion, Ă Abydos, et datant de Nagada III, est le support dâune gravure reprĂ©sentant un animal Ă©nigmatique. Cet animal a dĂ©jĂ Ă©tĂ© dĂ©signĂ© comme Ă©tant un oryctĂ©rope, Orycteropus afer, car il possĂšde indubitablement des caractĂšres anatomiques appartenant Ă cette espĂšce. Toutefois, il prĂ©sente Ă©galement des caractĂšres anatomiques de fennec, Fennecus zerda. Cette derniĂšre possibilitĂ© dâinterprĂ©tation en ferait alors la seule reprĂ©sentation connue Ă ce jour de fennec en Ăgypte pour les Ă©poques prĂ©dynastique et pharaonique.

An ivory label of a pottery coming from the king Scorpionâ tomb, to Abydos, and dating from Naqada III, carry a carving of an enigmatic animal. This animal was already point out like a Aardvak, Orycteropus afer, because it have beyond any doubt anatomical characteristics of this specie. However, it present equally anatomical characteristics of Fennec, Fennecus zerda. This last possibility of interpretation do of it the only representation of the Fennec known until now in Egypt during Predynastic and Pharaonic epochs.

An ivory label of a pottery coming from the king Scorpionâ tomb, to Abydos, and dating from Naqada III, carry a carving of an enigmatic animal. This animal was already point out like a Aardvak, Orycteropus afer, because it have beyond any doubt anatomical characteristics of this specie. However, it present equally anatomical characteristics of Fennec, Fennecus zerda. This last possibility of interpretation do of it the only representation of the Fennec known until now in Egypt during Predynastic and Pharaonic epochs.

Pages

193-213

Ătude de la stĂšle de PahĂ©rypedjet conservĂ©e au MusĂ©e du Caire et de quelques titres qui y sont mentionnĂ©s.

Ătude de la stĂšle de PahĂ©rypedjet conservĂ©e au MusĂ©e du Caire et de quelques titres qui y sont mentionnĂ©s.

Study of the stele of Pahérypedjet of the Museum of Cairo and of some titles which are mentioned in the stele.

Study of the stele of Pahérypedjet of the Museum of Cairo and of some titles which are mentioned in the stele.

ENiM 4 - 2011 (ISSN 2102-6629)

Sommaire

Pages

1-37

Le conte des Deux FrĂšres a toujours posĂ© problĂšme Ă ses commentateurs. On sait, depuis la publication du P. Jumilhac par J. Vandier, quâil faut le mettre en relation avec les XVIIe et XVIIIe nomes de Haute-Ăgypte. Une analyse tenant compte plus systĂ©matiquement des dieux, des rites et des interdits mentionnĂ©s dans le P. Jumilhac permet de mieux cerner sa signification.

Le conte des Deux FrĂšres a toujours posĂ© problĂšme Ă ses commentateurs. On sait, depuis la publication du P. Jumilhac par J. Vandier, quâil faut le mettre en relation avec les XVIIe et XVIIIe nomes de Haute-Ăgypte. Une analyse tenant compte plus systĂ©matiquement des dieux, des rites et des interdits mentionnĂ©s dans le P. Jumilhac permet de mieux cerner sa signification.

The tale of Two Brothers always raised problem to his commentators. We know, since the publication of P. Jumilhac by J. Vandier, that it is necessary to put it in connection with the XVIIth and XVIIIth nomes of Upper Egypt. An analysis taking into account more systematically gods, rites and prohibitions mentioned in P. Jumilhac allows to understand better its meaning.

The tale of Two Brothers always raised problem to his commentators. We know, since the publication of P. Jumilhac by J. Vandier, that it is necessary to put it in connection with the XVIIth and XVIIIth nomes of Upper Egypt. An analysis taking into account more systematically gods, rites and prohibitions mentioned in P. Jumilhac allows to understand better its meaning.

Pages

39-49

Cet article a pour but de donner une interprétation nouvelle des tablettes Rogers et Mac

Cullum, sur la base dâune analyse proprement juridique. Il offre par consĂ©quent un point de

vue différent sur le rÎle des chaouabtis/ouchebtis dans les croyances funéraires.

Cet article a pour but de donner une interprétation nouvelle des tablettes Rogers et Mac

Cullum, sur la base dâune analyse proprement juridique. Il offre par consĂ©quent un point de

vue différent sur le rÎle des chaouabtis/ouchebtis dans les croyances funéraires.

This paper aims to give a new interpretation of the Rogers and McCullum tablets on the basis

of a Specifically legal analysis. Consequently it offers a different point of view of the role of

shabtis/ushabtis in funerary beliefs.

This paper aims to give a new interpretation of the Rogers and McCullum tablets on the basis

of a Specifically legal analysis. Consequently it offers a different point of view of the role of

shabtis/ushabtis in funerary beliefs.

Pages

51-79

Cet article traite des structures spĂ©cifiques relatives aux croyances se rapportant au crocodile du Nil (Crocodylus niloticus Laurenti 1768), une espĂšce commune Ă tout le bassin versant du Nil et qui incarne le chĂątiment divin. AprĂšs avoir dressĂ© un arriĂšre-plan hiĂ©roglyphique, lexical, anthropologique et religieux relatif au crocodile, lâauteur souligne, Ă travers une sĂ©lection de sources hiĂ©roglyphiques, grecques et latines, lâexistence de plusieurs paradoxes. Le saurien est considĂ©rĂ© de deux façons antagonistes : 1°) comme un animal qui cause soit une mort divinisante, soit une mort dĂ©nonçant la culpabilitĂ© de la victime ; 2°) comme un animal qui incarne des forces divines nĂ©gatives et dont lâĂ©radication est nĂ©cessaire, car il est Ă lâorigine de multiples accidents. Des comparaisons avec lâunivers des reprĂ©sentations malgaches et dogons au sujet de ce saurien suggĂšrent lâexistence de structures parallĂšles de condamnations par le destin personnifiĂ©es par Crocodylus niloticus.

Cet article traite des structures spĂ©cifiques relatives aux croyances se rapportant au crocodile du Nil (Crocodylus niloticus Laurenti 1768), une espĂšce commune Ă tout le bassin versant du Nil et qui incarne le chĂątiment divin. AprĂšs avoir dressĂ© un arriĂšre-plan hiĂ©roglyphique, lexical, anthropologique et religieux relatif au crocodile, lâauteur souligne, Ă travers une sĂ©lection de sources hiĂ©roglyphiques, grecques et latines, lâexistence de plusieurs paradoxes. Le saurien est considĂ©rĂ© de deux façons antagonistes : 1°) comme un animal qui cause soit une mort divinisante, soit une mort dĂ©nonçant la culpabilitĂ© de la victime ; 2°) comme un animal qui incarne des forces divines nĂ©gatives et dont lâĂ©radication est nĂ©cessaire, car il est Ă lâorigine de multiples accidents. Des comparaisons avec lâunivers des reprĂ©sentations malgaches et dogons au sujet de ce saurien suggĂšrent lâexistence de structures parallĂšles de condamnations par le destin personnifiĂ©es par Crocodylus niloticus.

This paper addresses the specific structures relating to beliefs connected with the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus Laurenti 1768), a common species in the catchment basin of the Nile and which embodies divine punishment. After outlining a hieroglyphical, lexicological, anthropological and religious background relating to the crocodile, the author emphasizes, by means of a selection of hieroglyphic, Greek and Latin sources, the existence of several paradoxes. The saurian is considered according to two opposing ways : 1) as an animal which causes either a deifying death or a death expressing the guilt of the victim ; 2) as an animal embodying negative deities whose eradication is necessary since many accidents are caused by the saurian. Comparisons with the Madagascan and Dogon behaviours concerning this saurian suggest the existence of parallel death sentence structures based on fate and personified by Crocodylus niloticus.

This paper addresses the specific structures relating to beliefs connected with the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus Laurenti 1768), a common species in the catchment basin of the Nile and which embodies divine punishment. After outlining a hieroglyphical, lexicological, anthropological and religious background relating to the crocodile, the author emphasizes, by means of a selection of hieroglyphic, Greek and Latin sources, the existence of several paradoxes. The saurian is considered according to two opposing ways : 1) as an animal which causes either a deifying death or a death expressing the guilt of the victim ; 2) as an animal embodying negative deities whose eradication is necessary since many accidents are caused by the saurian. Comparisons with the Madagascan and Dogon behaviours concerning this saurian suggest the existence of parallel death sentence structures based on fate and personified by Crocodylus niloticus.

Pages

81-90

Cet article est consacrĂ© au remploi dâun jambage de porte en calcaire dur au nom de SĂ©sostris Ier ayant servi de support pour graver la deuxiĂšme stĂšle de Kamosis dĂ©couverte en 1954 Ă Karnak. Un rĂ©examen de la stĂšle au MusĂ©e de Louqsor et une plaque de verre des archives du Cfeetk (CSA/USR 3172 du Cnrs) datĂ©e de 1956 qui montre la stĂšle dans un meilleur Ă©tat de conservation ont permis de lever une partie des difficultĂ©s de lecture signalĂ©es et de proposer une nouvelle identification des divinitĂ©s reprĂ©sentĂ©es sur le jambage. Le dieu Amon et une dĂ©esse (que les restes du nom invitent Ă identifier Ă Mout ou Nekhbet) allaitant SĂ©sostris Ier sont reprĂ©sentĂ©s sur le premier registre et la dĂ©esse Bastet confĂ©rant la vie au roi est prĂ©sente sur le deuxiĂšme registre. Un examen des diffĂ©rents Ă©lĂ©ments Ă mĂȘme de prĂ©ciser la localisation dâorigine de ce jambage et les Ă©vĂ©nements ayant conduit Ă son remploi par Kamosis viennent conclure cette Ă©tude.

Cet article est consacrĂ© au remploi dâun jambage de porte en calcaire dur au nom de SĂ©sostris Ier ayant servi de support pour graver la deuxiĂšme stĂšle de Kamosis dĂ©couverte en 1954 Ă Karnak. Un rĂ©examen de la stĂšle au MusĂ©e de Louqsor et une plaque de verre des archives du Cfeetk (CSA/USR 3172 du Cnrs) datĂ©e de 1956 qui montre la stĂšle dans un meilleur Ă©tat de conservation ont permis de lever une partie des difficultĂ©s de lecture signalĂ©es et de proposer une nouvelle identification des divinitĂ©s reprĂ©sentĂ©es sur le jambage. Le dieu Amon et une dĂ©esse (que les restes du nom invitent Ă identifier Ă Mout ou Nekhbet) allaitant SĂ©sostris Ier sont reprĂ©sentĂ©s sur le premier registre et la dĂ©esse Bastet confĂ©rant la vie au roi est prĂ©sente sur le deuxiĂšme registre. Un examen des diffĂ©rents Ă©lĂ©ments Ă mĂȘme de prĂ©ciser la localisation dâorigine de ce jambage et les Ă©vĂ©nements ayant conduit Ă son remploi par Kamosis viennent conclure cette Ă©tude.

This article focuses on a hard limestone door jamb in the name of Senusret I reused for the second stela of Kamose uncovered in 1954 at Karnak. A new examination of the stela in the Luxor Museum and a glass photographs in the archives of CFEETK (SCA/USR 3172 Cnrs) dating from 1956 which shows the stela in a better state of preservation have eliminated some of the reported difficulties and allows us to propose a new identification of the deities represented on the door jamb. The god Amun and a goddess (who can be identify to Mut or Nekhbet) suckling Senusret I are represented on the first register and the goddess Bastet giving life to the king on the second register. A review of the elements able to specify the original location of the door jamb and the sequence of events that led to its reuse by Kamose concludes this study.

This article focuses on a hard limestone door jamb in the name of Senusret I reused for the second stela of Kamose uncovered in 1954 at Karnak. A new examination of the stela in the Luxor Museum and a glass photographs in the archives of CFEETK (SCA/USR 3172 Cnrs) dating from 1956 which shows the stela in a better state of preservation have eliminated some of the reported difficulties and allows us to propose a new identification of the deities represented on the door jamb. The god Amun and a goddess (who can be identify to Mut or Nekhbet) suckling Senusret I are represented on the first register and the goddess Bastet giving life to the king on the second register. A review of the elements able to specify the original location of the door jamb and the sequence of events that led to its reuse by Kamose concludes this study.

Pages

91-102

Depuis plus de 7000 ans, le baudrier croisĂ© est un Ă©lĂ©ment distinctif de la culture libyco-berbĂšre. Symbole de suprĂ©matie sociale et guerriĂšre, il est encore aujourdâhui fiĂšrement arborĂ© par les Touaregs. Alors, confrontĂ© Ă un baudrier similaire portĂ© par Pharaon et ses sujets, la question se pose de savoir sâil sâagit du mĂȘme vĂȘtement et, le cas Ă©chĂ©ant, quelle est sa raison dâĂȘtre en Ăgypte ancienne ?

Depuis plus de 7000 ans, le baudrier croisĂ© est un Ă©lĂ©ment distinctif de la culture libyco-berbĂšre. Symbole de suprĂ©matie sociale et guerriĂšre, il est encore aujourdâhui fiĂšrement arborĂ© par les Touaregs. Alors, confrontĂ© Ă un baudrier similaire portĂ© par Pharaon et ses sujets, la question se pose de savoir sâil sâagit du mĂȘme vĂȘtement et, le cas Ă©chĂ©ant, quelle est sa raison dâĂȘtre en Ăgypte ancienne ?

Since more seven thousand years, crossed baldric is a distinctive element of the libyco-berbere culture. Symbol of social and warlike pre-eminence, it is yet proudly worn by the Touaregs. So, confronted to a similar baldric worn by Pharaoh and his subjects, the question is asked to know if we talk about the same garment and if necessary, which the reason of its use in Ancient Egypt is?

Since more seven thousand years, crossed baldric is a distinctive element of the libyco-berbere culture. Symbol of social and warlike pre-eminence, it is yet proudly worn by the Touaregs. So, confronted to a similar baldric worn by Pharaoh and his subjects, the question is asked to know if we talk about the same garment and if necessary, which the reason of its use in Ancient Egypt is?

Pages

103-106

Ătude dâune table dâoffrandes en calcaire, exposĂ©e au MusĂ©e de lâagriculture Ă©gyptienne ancienne Ă Dokki, enregistrĂ©e sous le no 1354. Elle provient probablement de Deir el-MĂ©dineh et appartient au serviteur de la place de vĂ©ritĂ© Houy qui a vĂ©cu pendant la pĂ©riode Ramesside.

Ătude dâune table dâoffrandes en calcaire, exposĂ©e au MusĂ©e de lâagriculture Ă©gyptienne ancienne Ă Dokki, enregistrĂ©e sous le no 1354. Elle provient probablement de Deir el-MĂ©dineh et appartient au serviteur de la place de vĂ©ritĂ© Houy qui a vĂ©cu pendant la pĂ©riode Ramesside.

Study of a limestone offering-table, exposed in the Museum of old Egyptian agriculture in Dokki, recorded under No 1354. It comes probably from Deir el-MĂ©dineh and belongs to the servant of the place of truth Houy which lived during the Ramesside period.

Study of a limestone offering-table, exposed in the Museum of old Egyptian agriculture in Dokki, recorded under No 1354. It comes probably from Deir el-MĂ©dineh and belongs to the servant of the place of truth Houy which lived during the Ramesside period.

Pages

107-136

Le Naos des DĂ©cades, dĂ©diĂ© au dieu Chou, est un monument unique par sa collection de textes originaux et par la dĂ©coration extĂ©rieure de ses parois, consacrant une case a chacune des dĂ©cades de lâannĂ©e Ă©gyptienne. Chaque case montre cinq vignettes accompagnant un petit commentaire qui a Ă©tĂ© qualifiĂ© dâ« astrologique », et qui diffĂšre Ă chaque dĂ©cade. Ces notices font intervenir un « grand dieu », dont lâaction vise Ă dĂ©truire les populations ennemies, elles semblent de nature plus mythologique quâastrologique, et leur ensemble pourrait constituer lâun de ces « Livres de Chou » que le dieu confie Ă Sekhmet, faisant le dĂ©compte de ceux que la dĂ©esse et sa troupe de dĂ©cans doivent Ă©liminer. La place du monument dans lâastrologie Ă©gyptienne est discutĂ©e : alors que le commentaire concerne des populations entiĂšres, les vignettes et leurs lĂ©gendes intĂ©ressent le destin individuel et semblent relier le rĂ©sultat du jugement divin et donc lâavenir du ka Ă la position des astres dans le ciel. Ă cet Ă©gard, le monument pourrait reflĂ©ter, ou ĂȘtre le prĂ©curseur des systĂšmes astrologiques prĂ©disant le devenir dâaprĂšs la position variable des planĂštes, du soleil et des dĂ©cans selon les heures.

Le Naos des DĂ©cades, dĂ©diĂ© au dieu Chou, est un monument unique par sa collection de textes originaux et par la dĂ©coration extĂ©rieure de ses parois, consacrant une case a chacune des dĂ©cades de lâannĂ©e Ă©gyptienne. Chaque case montre cinq vignettes accompagnant un petit commentaire qui a Ă©tĂ© qualifiĂ© dâ« astrologique », et qui diffĂšre Ă chaque dĂ©cade. Ces notices font intervenir un « grand dieu », dont lâaction vise Ă dĂ©truire les populations ennemies, elles semblent de nature plus mythologique quâastrologique, et leur ensemble pourrait constituer lâun de ces « Livres de Chou » que le dieu confie Ă Sekhmet, faisant le dĂ©compte de ceux que la dĂ©esse et sa troupe de dĂ©cans doivent Ă©liminer. La place du monument dans lâastrologie Ă©gyptienne est discutĂ©e : alors que le commentaire concerne des populations entiĂšres, les vignettes et leurs lĂ©gendes intĂ©ressent le destin individuel et semblent relier le rĂ©sultat du jugement divin et donc lâavenir du ka Ă la position des astres dans le ciel. Ă cet Ă©gard, le monument pourrait reflĂ©ter, ou ĂȘtre le prĂ©curseur des systĂšmes astrologiques prĂ©disant le devenir dâaprĂšs la position variable des planĂštes, du soleil et des dĂ©cans selon les heures.

The Naos of the Decades is dedicated to the god Shu. It is a monument unique as to its collection of original texts and the decoration of its outside walls which contains a frame for each of the decades of the Egyptian year. Each of these frames displays five vignettes which accompany a short comment which was qualified as âastrologicalâ, and is different for each decade. These notes call a âgreat godâ for action to destroy enemy populations, and they seem more of a mythological than an astrological nature. The collection of these texts could constitute one of the âBooks of Shuâ which that god entrusted to Sekhmet, establishing a list of those that the goddess and her troop of decans is to eliminate. The position of the monument in Egyptian astrology is arguable: while the comment concerns entire populations, the vignettes and their legends deal with individual destiny and seem to link result of divine judgement and thus the future of the ka to the position of the stars in the sky. In this context, the monument could reflect or precede the astrological systems that foretell the future from the changing position of the planets, the sun and the decans according to the hours.

The Naos of the Decades is dedicated to the god Shu. It is a monument unique as to its collection of original texts and the decoration of its outside walls which contains a frame for each of the decades of the Egyptian year. Each of these frames displays five vignettes which accompany a short comment which was qualified as âastrologicalâ, and is different for each decade. These notes call a âgreat godâ for action to destroy enemy populations, and they seem more of a mythological than an astrological nature. The collection of these texts could constitute one of the âBooks of Shuâ which that god entrusted to Sekhmet, establishing a list of those that the goddess and her troop of decans is to eliminate. The position of the monument in Egyptian astrology is arguable: while the comment concerns entire populations, the vignettes and their legends deal with individual destiny and seem to link result of divine judgement and thus the future of the ka to the position of the stars in the sky. In this context, the monument could reflect or precede the astrological systems that foretell the future from the changing position of the planets, the sun and the decans according to the hours.

Pages

137-158

Le dieu Seth, comme lâillustrent bien les Textes des Pyramides, est une figure polysĂ©mique. Cette spĂ©cificitĂ© tient essentiellement Ă ce quâau Seth « ancien », le dieu de Noubet (Ombos, Nagada), protagoniste avec lâHorus de NĂ©khen (HiĂ©raconpolis) du mythe fondateur de la constitution de lâĂtat pharaonique, sâest superposĂ© un nouveau Seth hĂ©liopolitain, lâagresseur dâOsiris. Les thĂ©ologiens-thĂ©oriciens du pouvoir ont dĂ©libĂ©rĂ©ment jouĂ© sur cette homonymie afin de stigmatiser toute forme de contestation politique.

Le dieu Seth, comme lâillustrent bien les Textes des Pyramides, est une figure polysĂ©mique. Cette spĂ©cificitĂ© tient essentiellement Ă ce quâau Seth « ancien », le dieu de Noubet (Ombos, Nagada), protagoniste avec lâHorus de NĂ©khen (HiĂ©raconpolis) du mythe fondateur de la constitution de lâĂtat pharaonique, sâest superposĂ© un nouveau Seth hĂ©liopolitain, lâagresseur dâOsiris. Les thĂ©ologiens-thĂ©oriciens du pouvoir ont dĂ©libĂ©rĂ©ment jouĂ© sur cette homonymie afin de stigmatiser toute forme de contestation politique.

As it seems to be clear from the Pyramid Texts, the god Seth is a fundamentally polysemic character. This comes from the fact that a ânewâ Seth, the murderer of Osiris according to the Heliopolitan theology, has been superposed to the older Seth, the god of Nubet (Ombos, Nagada), the protagonist of the historiographic myth together with Horus of Nekhen (Hieraconpolis). This article try to show how this double character of Seth has been intentionally used against whoever would contest the pharaonic power.

As it seems to be clear from the Pyramid Texts, the god Seth is a fundamentally polysemic character. This comes from the fact that a ânewâ Seth, the murderer of Osiris according to the Heliopolitan theology, has been superposed to the older Seth, the god of Nubet (Ombos, Nagada), the protagonist of the historiographic myth together with Horus of Nekhen (Hieraconpolis). This article try to show how this double character of Seth has been intentionally used against whoever would contest the pharaonic power.

Pages

159-196

« Maltais, trophĂš, ktĂšsios... Remarques autour des figurines de chien en terre cuite dâĂgypte »

Le prĂ©sent article se propose dâidentifier la valeur emblĂ©matique des terres cuites de chiens maltais fabriquĂ©s en Ăgypte. Une origine iconographique propre au monde grĂ©co-romain a Ă©tĂ© confirmĂ©e (dĂšs le VIe-Ve siĂšcle av. J.-C.). Ensuite, il sâest agit de se demander comment ces objets de consommation courante ont pu ĂȘtre « lisibles » dans lâĂgypte grecque et romaine. La docilitĂ© et la trophĂš infantile initialement Ă©voquĂ©es par le chien maltais sont rĂ©investies dans le jeu des rapports sociaux prĂ©sidĂ©s par la notion de « parentalisation ». Ă cela sâajoute la valeur dâapprovisionnement alimentaire au cĆur des mĂ©canismes communautaires. Le rĂ©investissement est tel, que sous lâEmpire, le chien maltais plus souvent individualisĂ© quâassociĂ© Ă lâenfant-dieu Karpocrate / Harpocrate, passe de qualificatif (statut de la prime enfance) Ă entitĂ© pleinement autonome. En ce sens, la terre cuite de chien maltais pourra intĂ©grer les foyers (ktĂ©sios), les greniers Ă blĂ© (anatropheus), les fortins (trophĂš militaire)âŠ

Le prĂ©sent article se propose dâidentifier la valeur emblĂ©matique des terres cuites de chiens maltais fabriquĂ©s en Ăgypte. Une origine iconographique propre au monde grĂ©co-romain a Ă©tĂ© confirmĂ©e (dĂšs le VIe-Ve siĂšcle av. J.-C.). Ensuite, il sâest agit de se demander comment ces objets de consommation courante ont pu ĂȘtre « lisibles » dans lâĂgypte grecque et romaine. La docilitĂ© et la trophĂš infantile initialement Ă©voquĂ©es par le chien maltais sont rĂ©investies dans le jeu des rapports sociaux prĂ©sidĂ©s par la notion de « parentalisation ». Ă cela sâajoute la valeur dâapprovisionnement alimentaire au cĆur des mĂ©canismes communautaires. Le rĂ©investissement est tel, que sous lâEmpire, le chien maltais plus souvent individualisĂ© quâassociĂ© Ă lâenfant-dieu Karpocrate / Harpocrate, passe de qualificatif (statut de la prime enfance) Ă entitĂ© pleinement autonome. En ce sens, la terre cuite de chien maltais pourra intĂ©grer les foyers (ktĂ©sios), les greniers Ă blĂ© (anatropheus), les fortins (trophĂš militaire)âŠ

The purpose of this article is identifying the symbolic value of the Maltese dogs terracottas made in Egypt. An iconographic origin was confirmed for the Greco-Roman world (from VIth-Vth cent. B.C.). Then, it is of wondering how these objects of regular consumption were able to be âreadableâ in Greek and Roman Egypt. The docility and the infantile trophe initially evoked by the Maltese dog are reinvested in the social relationships, chaired by the notion of âparentalisationâ. In it is added the value of food supply, a main part of the community mechanisms. Under the Empire, the Maltese dog, more often individualized than associated with the child-god Karpocrates / Harpocrates, became a complete autonomous entity rather the qualifier it was initially (status of the infancy). This way, the terracotta of Maltese dog can join homes (ktesios), granaries (anatropheus), forts (military trophe)âŠ

The purpose of this article is identifying the symbolic value of the Maltese dogs terracottas made in Egypt. An iconographic origin was confirmed for the Greco-Roman world (from VIth-Vth cent. B.C.). Then, it is of wondering how these objects of regular consumption were able to be âreadableâ in Greek and Roman Egypt. The docility and the infantile trophe initially evoked by the Maltese dog are reinvested in the social relationships, chaired by the notion of âparentalisationâ. In it is added the value of food supply, a main part of the community mechanisms. Under the Empire, the Maltese dog, more often individualized than associated with the child-god Karpocrates / Harpocrates, became a complete autonomous entity rather the qualifier it was initially (status of the infancy). This way, the terracotta of Maltese dog can join homes (ktesios), granaries (anatropheus), forts (military trophe)âŠ

Pages

197-232

Le deuxiĂšme Ă©pisode du conte des Deux FrĂšres a lieu en PhĂ©nicie. Cette rĂ©gion est prĂ©sentĂ©e comme une sorte de monde funĂ©raire dans lequel Bata meurt et retourne Ă la vie. La structure est la mĂȘme que pour le premier Ă©pisode.

Le deuxiĂšme Ă©pisode du conte des Deux FrĂšres a lieu en PhĂ©nicie. Cette rĂ©gion est prĂ©sentĂ©e comme une sorte de monde funĂ©raire dans lequel Bata meurt et retourne Ă la vie. La structure est la mĂȘme que pour le premier Ă©pisode.

The second episode of the Tale of Two Brothers takes place in Phoenicia. This region is presented as a sort of funerary world in which Bata dies and returns to the life. The structure is the same than in the first episode.

The second episode of the Tale of Two Brothers takes place in Phoenicia. This region is presented as a sort of funerary world in which Bata dies and returns to the life. The structure is the same than in the first episode.

Pages

233-272

Le cercueil de Jt-nfr-Jmn, connu grĂące aux publications de J.-Fr. A. Perrot, est conservĂ© au MusĂ©e dâAquitaine Ă Bordeaux (Mesuret-8590). Sa dĂ©coration est semblable au cercueil de Tayouheret et, secondairement, Ă celui de Masaharta, dĂ©couverts tous les deux dans la premiĂšre cachette de Deir el-Bahari. Lâorganisation horizontale du dĂ©cor intĂ©rieur et les frises sur les bords extĂ©rieur et intĂ©rieur de la cuve rappellent les cercueils de SoutymĂšs, SĂ©ramon et Masaharta. Ces dĂ©tails apparaissent spĂ©cifiquement sur les cercueils du dĂ©but de la XXIe dynastie dont le cercueil de Jt-nfr-Jmn est un remarquable exemplaire. Une inhumation vers 1070-1060 av. J.-C. est proposĂ©e.

Le cercueil de Jt-nfr-Jmn, connu grĂące aux publications de J.-Fr. A. Perrot, est conservĂ© au MusĂ©e dâAquitaine Ă Bordeaux (Mesuret-8590). Sa dĂ©coration est semblable au cercueil de Tayouheret et, secondairement, Ă celui de Masaharta, dĂ©couverts tous les deux dans la premiĂšre cachette de Deir el-Bahari. Lâorganisation horizontale du dĂ©cor intĂ©rieur et les frises sur les bords extĂ©rieur et intĂ©rieur de la cuve rappellent les cercueils de SoutymĂšs, SĂ©ramon et Masaharta. Ces dĂ©tails apparaissent spĂ©cifiquement sur les cercueils du dĂ©but de la XXIe dynastie dont le cercueil de Jt-nfr-Jmn est un remarquable exemplaire. Une inhumation vers 1070-1060 av. J.-C. est proposĂ©e.

The Jt-nfr-Jmnâs coffin, known from the J.-Fr. A. Perrotâs publications, is conserved at The Aquitaine Museum in Bordeaux (Mesuret-8590). Its decoration is similar to the Taywheretâs coffin and secondarily to the Masahartaâs one, found both in the first cache of Deir el Bahri. The horizontal organization of interior decor and the friezes on the outside and inside edges of the case recall the coffins of Sutymes, Seramon and Masaharta. These details appear specifically on the coffins of the early 21st dynasty of which the Jt-nfr-Jmnâs coffin is a remarkable specimen. A burial about 1070-1060 BC is proposed.

The Jt-nfr-Jmnâs coffin, known from the J.-Fr. A. Perrotâs publications, is conserved at The Aquitaine Museum in Bordeaux (Mesuret-8590). Its decoration is similar to the Taywheretâs coffin and secondarily to the Masahartaâs one, found both in the first cache of Deir el Bahri. The horizontal organization of interior decor and the friezes on the outside and inside edges of the case recall the coffins of Sutymes, Seramon and Masaharta. These details appear specifically on the coffins of the early 21st dynasty of which the Jt-nfr-Jmnâs coffin is a remarkable specimen. A burial about 1070-1060 BC is proposed.

Pages

273-290

Rappel historique, analyse et essai d'identification des diverses fouilles entreprises à Atfih au début du XXe siÚcle. Quelques informations relatives à l'histoire et l'organisation du site sont mises en exergue.

Rappel historique, analyse et essai d'identification des diverses fouilles entreprises à Atfih au début du XXe siÚcle. Quelques informations relatives à l'histoire et l'organisation du site sont mises en exergue.

Historical reminder, analysis and attempt of identification of the various excavations undertaken to Atfih at the beginning of the XXth century. A few informations relating to the history and the organization of the site are highlighted.

Historical reminder, analysis and attempt of identification of the various excavations undertaken to Atfih at the beginning of the XXth century. A few informations relating to the history and the organization of the site are highlighted.

ENiM 5 - 2012 (ISSN 2102-6629)

Sommaire

Pages

1-6

Publication dâune statuette fragmentaire dâAmenmes, fils de Paouia (fin de la XIXe dynastie et dĂ©but de la XXe), conservĂ©e Ă lâOriental Museum, UniversitĂ© de Durham. Cet objet complĂšte le dossier de ce personnage dĂ©jĂ bien connu.

Publication dâune statuette fragmentaire dâAmenmes, fils de Paouia (fin de la XIXe dynastie et dĂ©but de la XXe), conservĂ©e Ă lâOriental Museum, UniversitĂ© de Durham. Cet objet complĂšte le dossier de ce personnage dĂ©jĂ bien connu.

Publication of a fragmentary statuette of Amenmes, son of Ouia (end of the XIXth dynasty and beginning of the XXth), kept in the Oriental Museum, University of Durham. Amenmes is already known by the other documents.

Publication of a fragmentary statuette of Amenmes, son of Ouia (end of the XIXth dynasty and beginning of the XXth), kept in the Oriental Museum, University of Durham. Amenmes is already known by the other documents.

Pages

7-18

Au IIIe siĂšcle avant JĂ©sus-Christ, plusieurs citĂ©s de GrĂšce dĂ©cidĂšrent dâadopter le nom dâune souveraine Ă©gyptienne dâorigine macĂ©donienne. Deux souveraines furent concernĂ©es : ArsinoĂ© II Philadelphe et ArsinoĂ© III Philopator. Lâacte de changer de nom â la mĂ©tonomasie â nâĂ©tait pas un acte anodin pour ces citĂ©s ancestrales ; les facteurs qui y prĂ©ludĂšrent et les consĂ©quences qui en rĂ©sultĂšrent sont Ă©tudiĂ©s dans cet article.

Au IIIe siĂšcle avant JĂ©sus-Christ, plusieurs citĂ©s de GrĂšce dĂ©cidĂšrent dâadopter le nom dâune souveraine Ă©gyptienne dâorigine macĂ©donienne. Deux souveraines furent concernĂ©es : ArsinoĂ© II Philadelphe et ArsinoĂ© III Philopator. Lâacte de changer de nom â la mĂ©tonomasie â nâĂ©tait pas un acte anodin pour ces citĂ©s ancestrales ; les facteurs qui y prĂ©ludĂšrent et les consĂ©quences qui en rĂ©sultĂšrent sont Ă©tudiĂ©s dans cet article.

Several cities of Greece decided to renew their denominations with the name of a macedonian queen in the third century BC. Two rulers were concerned: Arsinoe II Philadelphos and Arsinoe III Philopator. The act of changing its name was not insignificant for these ancestral

cities. This article deals with the reasons and the consequences of this phenomenon.

Several cities of Greece decided to renew their denominations with the name of a macedonian queen in the third century BC. Two rulers were concerned: Arsinoe II Philadelphos and Arsinoe III Philopator. The act of changing its name was not insignificant for these ancestral

cities. This article deals with the reasons and the consequences of this phenomenon.

Pages

19-30

Le but de lâarticle est Ă la fois de prĂ©senter une synthĂšse gĂ©nĂ©rale du contenu du papyrus du Brooklyn Museum n° 35.1446 et de prĂ©ciser le statut des quelque 95 personnes qui figurent sur la liste du verso. Il sâavĂšre que celles-ci sont toutes dâorigine syro-palestinienne et que leur venue en Ăgypte sâinscrit dans le cadre dâune politique dâimmigration soutenue par les rois des XIIe-XIIIe dynasties.

Le but de lâarticle est Ă la fois de prĂ©senter une synthĂšse gĂ©nĂ©rale du contenu du papyrus du Brooklyn Museum n° 35.1446 et de prĂ©ciser le statut des quelque 95 personnes qui figurent sur la liste du verso. Il sâavĂšre que celles-ci sont toutes dâorigine syro-palestinienne et que leur venue en Ăgypte sâinscrit dans le cadre dâune politique dâimmigration soutenue par les rois des XIIe-XIIIe dynasties.

The aim of this paper is to present a general summary of the contents of P. Brooklyn Museum n° 35.1446 and to clarify the status of some ninety-five people who appear in the list on the verso. It turns out that all of them are Asiatics and that their entry into Egypt was part of an immigrapion policy upheld by the Kings of the XIIth-XIIIth Dynasties.

The aim of this paper is to present a general summary of the contents of P. Brooklyn Museum n° 35.1446 and to clarify the status of some ninety-five people who appear in the list on the verso. It turns out that all of them are Asiatics and that their entry into Egypt was part of an immigrapion policy upheld by the Kings of the XIIth-XIIIth Dynasties.

Pages

31-37

Analyse dâune Ă©pithĂšte obscure provenant du temple dâEsna. Deux nouvelles attestations permettent la traduction suivante : « la voĂ»te cĂ©leste nâest quâune partie de lui / dâelle » (gb.t ?y ?.t jm=f / jm=s). Des expressions semblables se rapportant aux membres divins sont Ă©galement analysĂ©e.

Analyse dâune Ă©pithĂšte obscure provenant du temple dâEsna. Deux nouvelles attestations permettent la traduction suivante : « la voĂ»te cĂ©leste nâest quâune partie de lui / dâelle » (gb.t ?y ?.t jm=f / jm=s). Des expressions semblables se rapportant aux membres divins sont Ă©galement analysĂ©e.